I have spent quite a lot of time lately making an engine for a game idea I have, but the result I got wasn’t exactly what I had in mind. This post is my opinion on engine development vs game development based on my experiences over the last few weeks.

Make games, not engines

This was a phrase I saw being thrown around in many of the communities I frequently look at that I’ve only recently noticed after working on a personal project for a bit. If you’ve been following me, you will have noticed that I made ReduxForGames using code I have written from either scratch or from tutorials. This was by no means no easy task and I actually feel pretty exhausted. As I have said, the phrase ‘know thyself’ means a lot to me, and so working on an engine really made me question what I was and wasn’t confident or comfortable with in terms of the level of depth I was willing to go into with games development.

Alacrity ported into my own SDL and OpenGL engine.

It started out with curiosity — I wanted to see what our tutor had really done for us in our DirectX module at University by doing it myself. I figured I had already done a bit of OpenGL for a maths module and that SDL couldn’t have been too hard to learn (it wasn’t). As I got deeper and deeper and my lust for making flexible code grew, the engine quickly became saturated with code I was no longer fully understanding. It is important to learn from anything you write whether it was a genuine solution from you or a nudge from someone else. I hated the thought of not knowing how my Model class truly worked with index buffers etc. I had spent many all nighters trying to get code to work that I didn’t even really get in the first place.

I had always thought that a game is created from an engine, but in reality the engine is a by-product of the games development. To contradict myself, I actually did know this before I embarked on this project but it quickly blurred from my mind as I started working. While I knew the fact, I didn’t believe it. There is a crucial difference, and this difference was the very thing that is making me feel bummed out as I’m writing this. While I knew that the Unreal Engine was made with Unreal Tournament and that the Source Engine evolved with the Half Life series I seemed to forget that I should have been focusing on my game rather than the engine. It wasn’t long before I was trying to make my engine flexible and feature packed when I could have been making my game.

Making an engine is hard

Making an engine is no easy feat. I guess after making a very, very simple engine taught me that. Its not just about making a wrapper for your initialise(), update() and draw() functions. There is an absolutely massive amount of code beneath the surface — the graphics rendering is what I found particularly tough. I was told that everything I knew about OpenGL was actually old news and that I needed to look at modern techniques for OpenGL implementation (try learnOpenGL — it was the best thing I could find). On top of getting the engine working you need it to be efficient. Sure, 2D games may be an entirely different ball game to 3D games and you can slack on the efficiency bit but I actually felt really guilty for not attempting to dive deeper into vertex buffers and optimisation.

I actually was inspired by Darkest Dungeon to try and make my own engine. I accepted that it wasn’t going to be good but I at least wanted to make something on my very own so that I could say to people that my game was actually all me. I voided this very dream though when I realised I had no clue what I was doing and that I needed help. 4Chan and Discord communities are great for networking and if you pick your friends right they won’t have any problems looking at code once in a while. It got to the point where I was relying on others to help me figure out my own mistakes, I hated it.

What’s wrong with Unity or Unreal?

Nothing whatsoever. However I personally despise Unity and using Unreal made me feel deprived of my programmer’s enthusiasm. I know you can work in C++ for Unreal but I really didn’t feel the same. After trying out Monogame I realised that I really liked starting from scratch and working with no GUI and just pure code. Little did I know that there’s a big difference between ‘from scratch’ and from scratch. While I can say I have learned a lot from trying, I do not think I will try the combination of SDL + OpenGL on my very own again for a while. The tipping point was that I wanted the game I wanted to make to be moddable, and that I heard using Lua was a good way of going about doing this.

For those who aren’t really sure what I’m on about, Lua is a scripting language which you run on top of your engine. You could create all your functions in C++ and call them using Lua — the idea being that you write your game in simple scripts that modders (if you so choose) could come along and switch it up a bit. Obviously you’re in control over how much of your code you give to Lua and how much you keep reserved for the engine. I tried implementing this into my own engine, breaking most of its functionality and invalidating all the comments I had made. It was painful but that was my new goal.

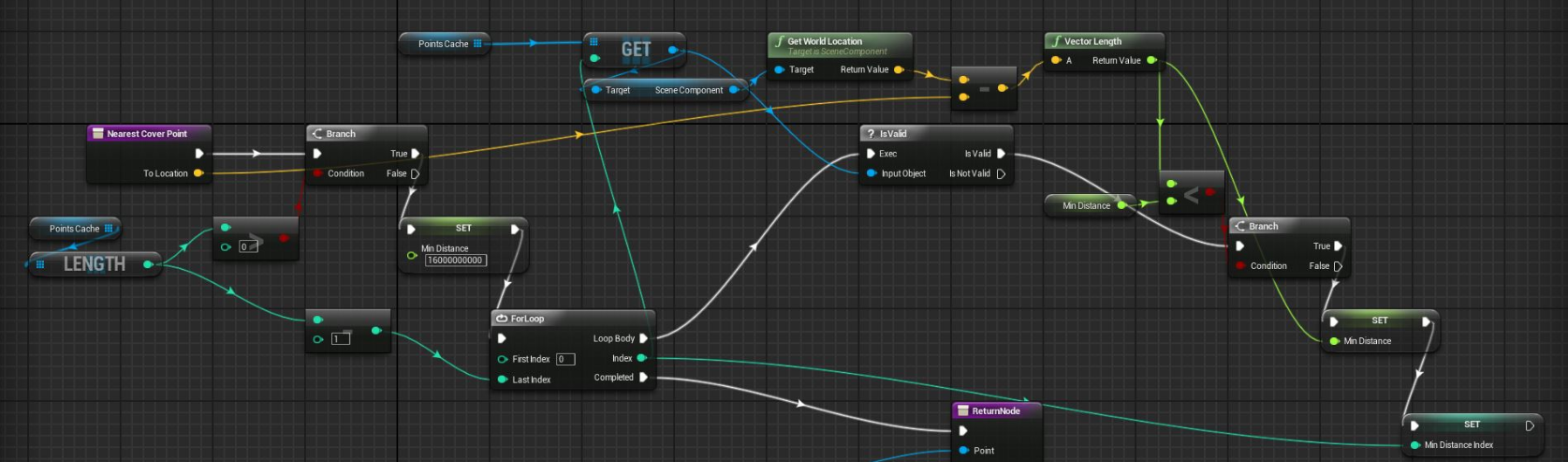

Unreal Engine visual scripting.

If you like Unity or Unreal then use them to your hearts content. Tools are tools and you shouldn’t feel pressured into using something else just because another programmer dislikes it. However, there is a big difference between a personal engine made for a game and engines like Unity or Unreal. Unity and Unreal are made to be flexible so that they can be accessible, affordable, useful and enjoyable for any programmer or team working on any game. This also means however, that functionality you don’t necessarily need is still loaded into your game. I’m generalising a bit and there may be safeguards to stop this being an issue, however these engines are no push overs. They are big for a reason, they can do so much that they can handle nearly everyone’s needs.

I want to specialise with 2D games when programming alone and I really didn’t want to get Unreal or Unity involved. I want to try and be as lightweight as possible ideally and I am against the idea of having to do things ‘the Unreal way’. However, the engine I was crafting started getting a life of its own — I was implementing classes just in case I needed them even know I knew I wasn’t going to have any 3D assets into my game. It was almost as if I was trying to rival the amount of scenarios my engine will be used and that one day I might use it to make a 3D game or a game that uses touch screen rather than a mouse and keyboard.

Engine vs No Engine

Until today, I didn’t realise that ‘no engine’ could mean so many different things. Whatever you want to call it, you will always have (or have built) something that takes on the responsibility of an engine by the completion of your game. Like just like a car, whether you choose to buy an engine or not doesn’t matter — the car won’t be a car unless it has an engine to drive it forward when its done and that you have to get one from somewhere. If you choose not to use Unity or Unreal then that’s fine, but the question is still up for debate. Are you really going to go and make your own engine? How many team members do you have who can help? Do you have any prior knowledge of making an engine? What languages will be used and what dependencies will there be?

Monogame: a framework for game development in C#.

Frameworks are still a thing. Monogame for C# and LÖVE for Lua are just some examples of ones I have been looking up lately. SDL and SFML are libraries. These just provide methods of handling input and window creation, for instance, but don’t actually do much for you. They do have graphics renderers built in but OpenGL can also be used to get a bit more advanced (I got greedy and took this route — be careful and know what you’re getting into before trying it yourself). A framework takes some of the pressure off of you by implementing several crucial pieces of functionality for you — Monogame handles sprite batching and the content pipelining for you as opposed to you having to implement a spritebatch method yourself in OpenGL, for instance.

Think of a framework as the step above a library — someone has compiled lots of libraries for you and made them work in harmony and as long as you stick to their framework you will be working on the same foundations as anyone else using said framework. A library is just a handful of functions that get into the nitty gritty of a program’s basic functionality and it will be up to you to decide on which libraries you import and use in your project. If it helps, you choose to call functions in the library and you are in control, but a framework calls upon you to call its functions in a specific way.

Last thoughts

Remember, the folks down at Epic (the people who maintain the Unreal Engine) have teams and teams of people dedicated to the ongoing development, maintenance and testing of the engine. If you’re reading this, there’s a chance that you’re considering making an engine so that you could make a game on your own, just like me. It is important to keep in mind that behind most frameworks, libraries and engines you see out there will be some sweaty nerds coding away to make it easier and more appropriate for you to use their work. If you want to make a game, make a game, but please bear in mind the gravity involved with creating something like an engine. I underestimated it massively.

If there’s one takeaway from all of this, its that I now know what I’m actually looking for in an engine/framework/library and that I know that I’m not going anywhere near OpenGL based engine work for a long time! This has all been my opinion, however, I really do feel the urge to discourage people who want to make a game from making their own engine. By all means, make an engine for academic purposes like I have done, show it off and say you gave it a go, however, if the game is the result you’re wanting then choose a framework or engine that matches your requirements. If these requirements are not matchable then maybe you need to get a team together and work hard on a prototype engine. Make sure that the game comes first and only implement the necessities into your engine — don’t repeat my mistakes!