GitHub repository for Hogs of War: Level Editor can be found here.

What is this?

In my final year of university, we had an assignment to make either a game or a tool, and so I took tried something new and made a cross-platform tool that allows for the visualisation and manipulation of Hogs of War map files. This was around the same time I was working on the 4D Geometry Viewer and so I re-used parts of the code base to speed up the process so I could focus on the meat of both projects.

At the time, the my computer science course was blessed by one of the programmers for Hogs of War. I was lucky enough to get to know him, learn from him, and have him as my supervisor for my thesis and I am very grateful for the time I spent in his sessions. When this assignment was revealed, there was discussion that there could be an opportunity to work with the source code for Hogs of War and maybe make some kind of tool, and so I decided to take on that challenge.

The other students worked on games in groups, but I was on my own for this assignment, and so to keep things fair it was decided that I’d be assessed slightly differently to factor in the need to fully communicate and plan the project to others. One of the just-graduated masters students was considered my ‘client’ for the assignment as he had also done work with the Hogs of War source code and was doing further work with it. My objective was to listen to the kinds of things he’d find useful, translate his requirements into milestones and then use HacknPlan to manage the project so that he could see my progress.

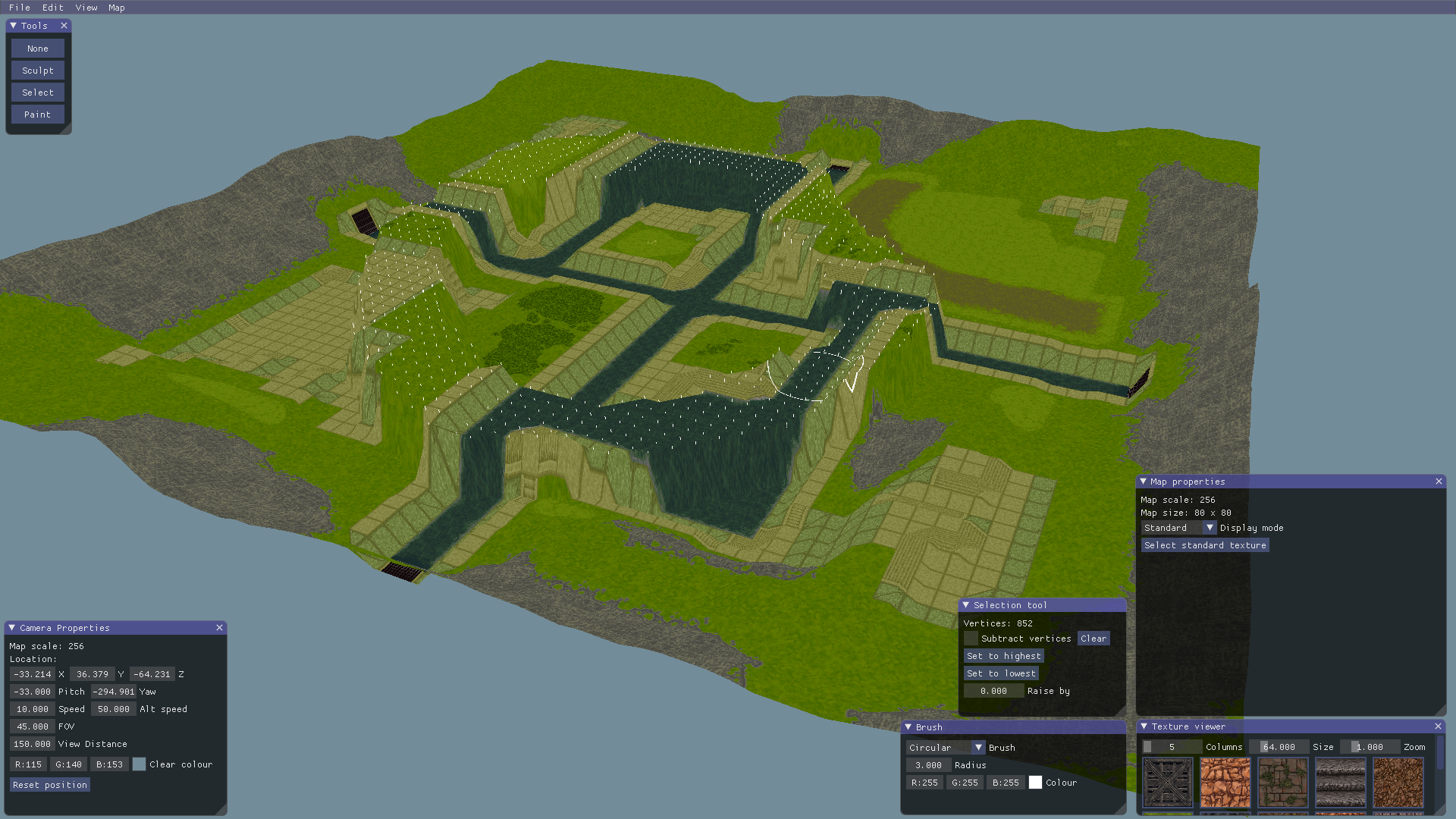

I successfully completed the assignment and felt quite proud at what I had made. It took the form of a level editor; one capable of sculpting and painting the various landscapes found within the old game files of Hogs of War. In the next section you will find a few videos previewing some of the features of what I had produced over the course of the assignment.

Features

Sculpting

The first task of the assignment was simply to load one of the map files of Hogs of War. The source code was, of course, proprietary, so I won’t go into the details of the difficulty I encountered trying to read the decade-old source code. My solution was to load the vertices into my own representation of a map to make it easier to edit, that way the only time I had to touch the old source code was when I needed to load or save a map to a file. In order to see whether I loaded a file correctly, I also needed to render it. Once I had a basic heightmap visualised on screen, everything started falling into place.

The first feature I wanted to implement was simply manipulating vertices with a normal ‘sculpting’ tool — you click and the ground bubbles upwards (or downwards, depending on the settings). Since the tool operates on vertices of the heightmap, I made the decision to draw ‘sticks’ to represent each individual vertex so that it was clear as to why the ‘circle’ shape didn’t raise a perfect circle of terrain. You can see these in the video below:

The sculpt tool can be used to raise and lower vertices in an adjustable brush. Holding the Shift key keeps the tool in place to avoid accidentally altering the heightmap.

To make sure that these changes were correctly applied to the map file, I had to demonstrate that I could open a map, edit it, save it and then re-open it to see the changes perfectly recreated.

Editing

The second big feature I implemented was something I noticed from the sculpting feature — the ability to be more specific about which vertices to raise / lower. This was the ‘selection’ tool. This became the best way to edit maps, since you could select vertices without mutating the map and then edit them in bulk. The video below illustrates this better than I can explain it:

The selection tool separates the selection of vertices from their modifications. Once a selection has been made, the tool can be used to modify all selected vertices at once.

The ability to undo and redo was also added around this time, since I was able to be encapsulate an ‘edit’, and so the undo-chain was as simple as applying the same transformation in reverse. This was a little bit trickier with the sculpting tool since that was one long continuous mutation, but all I needed to do was record the net change in height for each vertex.

Data visualisation

One of the later changes I made was the ability to change the appearance of the terrain by literally ‘painting’ textures onto it. To do this, I wanted to experiment with a splatmap system where each colour represented a different texture, these pairings could be configured with a drag-and-drop system. Once I could see and use the splatmap system, texture painting would be a case of adjusting the colours of these splatmaps.

The map can be rendered using a single texture in standard mode or by using multiple in enhanced mode. The splatmaps used in enhanced mode can also be viewed.

Texture painting

Texture painting was the one feature I wasn’t totally happy with — while it worked, the way it interacted with the undo functionality made it inefficient. This tool didn’t operate on vertices and instead operated on the splatmap textures themselves, meaning that potentially thousands of pixels could be adjusted each second of the paint tool being activated. Trying to record the net change of state for each pixel obviously made this a very intensive process, which is quite funny since the process of actually changing the texture and re-uploading it to the GPU was quite lightweight by comparison.

One of the potential optimisations I wanted to implement was to record the position and details of the brush each frame rather than the affected pixels — while this would be inefficient for vertex manipulation (as there’s a lot less affected vertices than the number of potential frames), it’d be much more efficient for pixel painting. Unfortunately, the deadline of the assignment was coming up and I decided to invest my time into other assignments as at this point I was fairly happy with the progress I had made.

The splatmaps used in enhanced rendering can be edited with the paint tool. Textures in the map properties panel can be clicked to quickly configure the tool to apply it to the map.

Conclusion

The assignment went really well and I had an absolute blast playing software-dev for the first time! It was an interesting experience applying the skills I had learned from games in a different way. It also opened my eyes to how enjoyable I’d find working on tooling in a job scenario, such as possibly making an in-house plugin for the Unreal Engine or something!

Thanks for reading!