GitHub repository for my thesis can be found here.

“The path to the right decision: An investigation into using heuristic pathfinding algorithms for decision making in game AI”

This was the title and topic of my well-received final year project for my final year of my masters degree. This investigation involved repurposing a generic implementation of the A* algorithm for decision making as opposed to terrain traversal. In this post, I will summarise what I have already written, so if you’re interested in the academic version then please read the full thesis (available online).

Background

Search algorithms

A search algorithm is a recursive method designed to find a match for a piece of data within a collection such as an array, graph or tree. A piece of data is provided and the search algorithm typically returns whether it is present and it’s location. Dijkstra’s algorithm is a search algorithm that operates on trees and graphs (which are then interpreted as trees). The algorithm calculates the shortest difference from any node on the graph to any other node, and can be terminated early to avoid unnecessary computation if a destination is provided and found.

Comparison of Dijkstra’s algorithm and the A* algorithm.

A* is an improvement of Dijkstra’s algorithm — while it doesn’t stray far from how Dijkstra’s algorithm works it does extend the algorithm using what’s known as a heuristic approach. In a pathfinding situation, a heuristic function could estimate the distance to the goal, by ignoring walls and measuring in a straight line, to direct the algorithm in the right direction and avoid evaluating routes that travel in the wrong direction to make the process more efficient.

This heuristic component of A* transforms it into a family of algorithms where applying a different heuristic selects a different algorithm.

This heuristic component of A* transforms it into a family of algorithms where applying a different heuristic selects a different algorithm, moreover, implementing A* and using a heuristic that returns a constant value for all nodes reverts A* back into Dijkstra’s algorithm. Conversely, implementing a well-designed heuristic method can be used to guarantee optimal solutions, and using a heuristic that is somewhere in-between can output results with varying degrees of accuracy in exchange for faster execution.

The implementation of a good heuristic can be difficult, as making the heuristic take more factors into account for accuracy has the drawback of making the algorithm less efficient overall with the heuristic being frequently used throughout the process.

Traversing decisions

In this project, the AI will be pathfinding through decisions and not locations. While the AI will still be moving through the map, it is doing so because it is deciding to, and not simply calculating a path. Much like a decision tree for game AI, each node in the traversal graph will represent an action for the AI to take and the AI will be generating a plan-of-action by connecting these nodes.

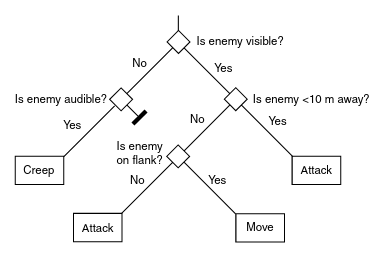

An example of a decision tree used in Game AI.

When the game world has been processed, the actions a character can perform have been laid out and the methods of evaluating courses of action have been provided, the only things remaining that A* needs to function are the start and goal node states for the actual decision. The starting state is trivial as it is simply the current state of the character and world; the goal state node requires more consideration than that though. For game AI though, the goal needs to represent how the character or world should be — or rather, the objective outcome of the decision making process.

This objective can be difficult to ascertain as a goal node could represent anything; what seems to be a simple goal such `win the game’ becomes a rigorous series of tests to both calculate the cost reaching the goal than another. On the other hand, objectives that are too small or disconnected may not combine correctly to form this over-arching goal of winning the game. A balance is needed, whether that means the objective is to chase the player or defend an area, the objective needs to be focused on winning without being vague.

Another talking point regarding goals is the amount of designated goal state nodes in the graph. There is typically only a single goal in standard pathfinding, but it is possible, maybe even advantageous, for some games to contain multiple goal nodes in a graph. Having multiple goals and goal types would grant the ability for the AI to re-route to a different goal if it’s easier and therefore accomplish the same task in multiple different ways without creating generic goals; this has its drawbacks though, one being the need for a more intricate and potentially confusing implementation and design of the AI needs, the other being the creation of balancing difficulties to ensure goals are prioritised as expected.

Defining the notion of cost

Cost, sometimes referred to as weight, is a term that will continue to be used when talking about A* as it is the the metric that governs the searching process. Cost doesn’t have to be a numeric value, as long as it can be compared and combined correctly with other cost values. However, one numeric restriction of cost is that it cannot, or rather should not, be negative.

The method A* uses to determine if a route should be expanded before another is if its cost value is lower — when only positive values are added together it is assumed that costs cannot decrease in value. While in mathematics it is entirely possible and valid for these values to be negative, the problems that make this necessary are not applicable to games.

Some decisions are more troublesome to weigh than others; with the constraint of non-negativity, what would the cost be of an ability that regenerates mana instead of expending it? The only way to apply reductions to values in this way would be to have a baseline cost for an action and then add or subtract from it, however, this does mean that this baseline value would dictate the maximum value of the reduction and so forward planning is necessary to ensure that all reductions can be applied in a balanced way.

Another difficult type of decision to way are ones that don’t have inherent characteristics; with a good goal for AI being unpredictable, surprising behaviour, how would the incentive for performing strategies like flanking and ambushing be created, and how would it compare to the cost for attacking an enemy directly head-on?

In this project, penalties were used to represent the cost of performing an action. Shooting an ally or walking into the range of an enemy unit resulted in penalties that could be tweaked per AI. It was hoped that these penalties would give the AI a sense of direction and that it would try to minimise incurring these penalties while making decisions.

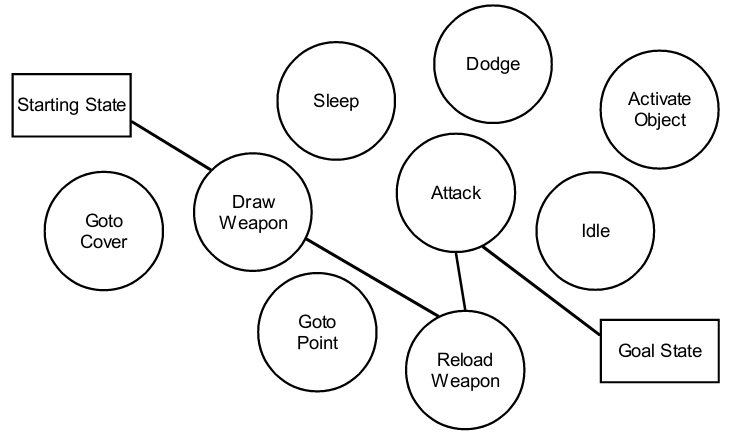

Comparisons with GOAP

During this project, I researched a very similar game AI implementation named Goal Oriented Action Planning (GOAP) by Jeff Orkin. The premise is the same; instead of navigating geometry, A* is used to navigate an abstract space where the nodes in the graph represent decisions. The main difference between GOAP and this project is that GOAP summarises an action into a single node — there is a layer of the AI that decides what actions would be relevant and / or how these actions are carried out, so going to cover or a point of interest is more focused. In my implementation, every possible target and tile to move to is a possible node, substantially increasing the size of the graph and relying on A*’s evaluation to choose the best nodes in the process.

Visualisation of GOAP’s graph of actions.

The project

Search algorithms such as A* are generic, maintainable and versatile and are therefore theoretically suitable replacements for FSMs and behaviour trees for implementing game AI. While GOAP does use A* for part of it’s decision making process, it isn’t a complete solution and still separates decision making from the pathfinding process. This is acceptable and valid as GOAP is for generating a sequence of actions whereas pathfinding is strictly for navigating the map in order to perform these actions. Unfortunately, some information found during pathfinding that could be considered useful for decision making is lost unless explicitly communicated — a decision might request to navigate to some location, but the path generated might be longer than expected and a different course of action could have been more appropriate. Without replanning, GOAP’s disconnect between these systems could result in the wrong decisions being made.

In this project, the mechanisms of the A* search algorithm were examined and re-engineered, through the substitution of input and output types, to investigate the modularity and adaptability of an AI that uses search algorithms to make decisions while actively involving pathfinding in the process as opposed to keeping these systems separate.

Several approaches to defining goals and heuristic methods were used to visualise the effects they have on a squad-controlling game AI. The aim of using this approach is to bring decision-making and pathfinding closer together and therefore simplifying the overarching process of perceiving, deciding and interacting in the game world.

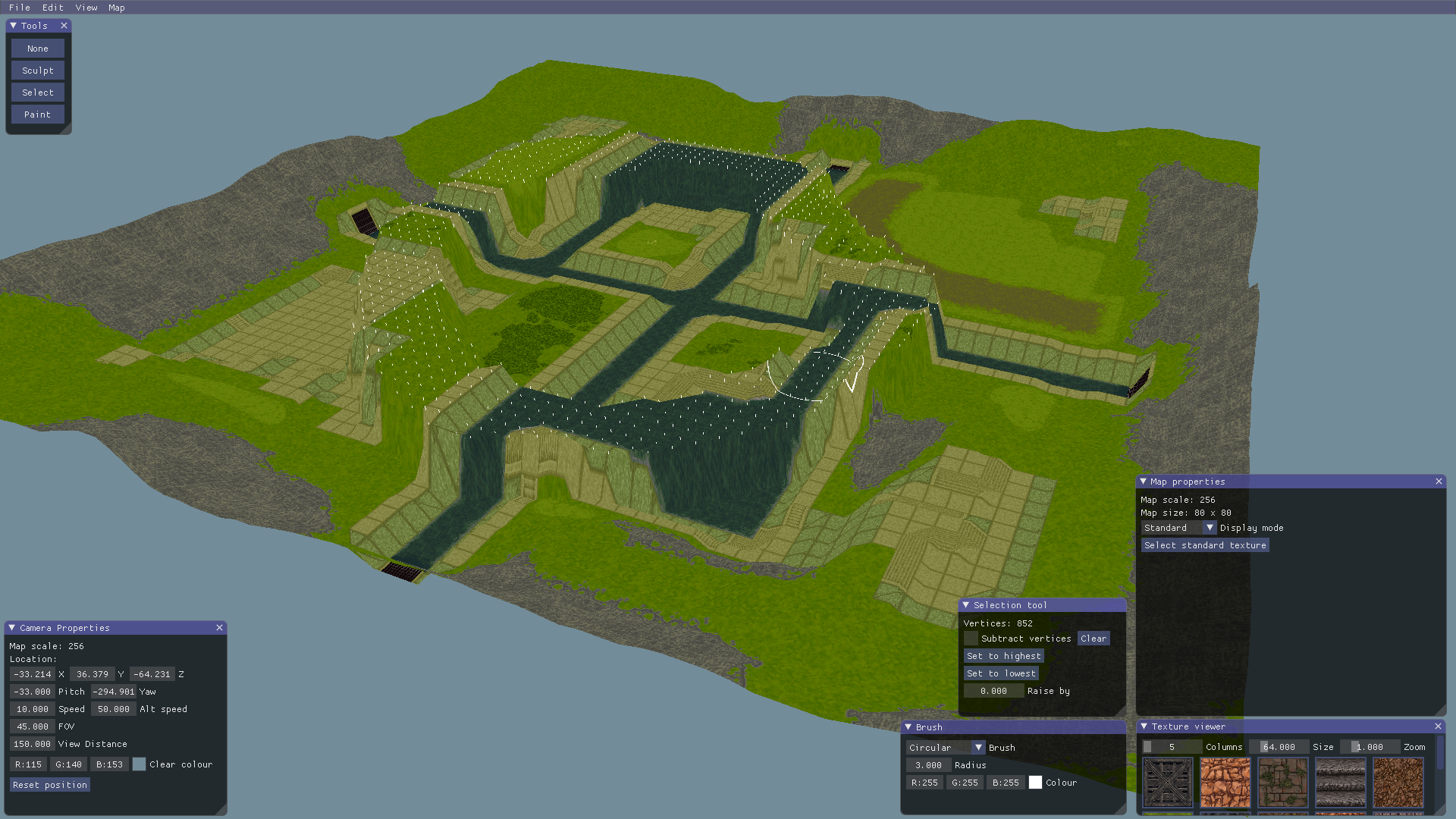

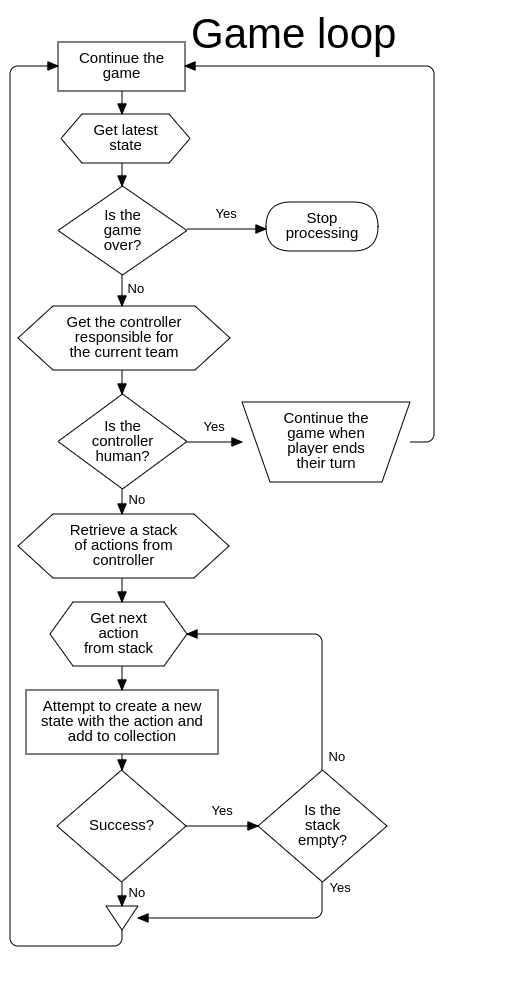

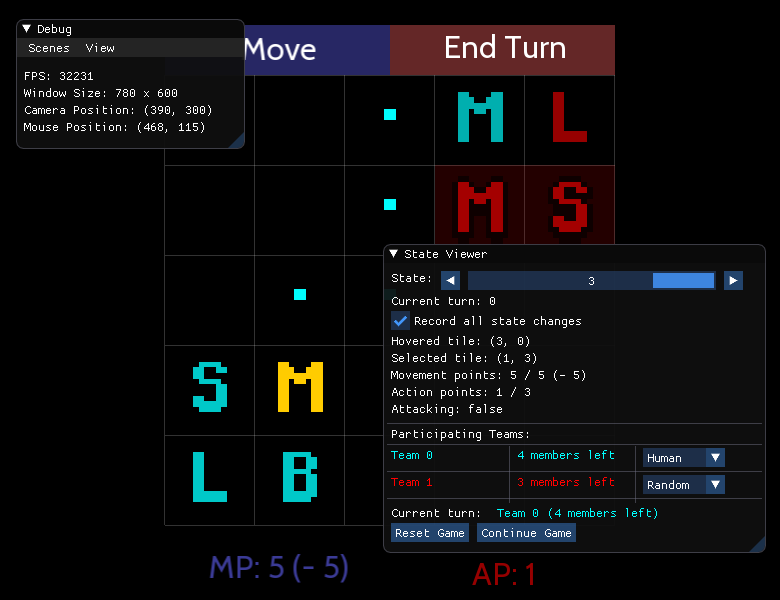

The strategy game

In order to test and observe this experimental AI, I decided to build a simple, turn-based strategy game for the AI to play. The rules of this game are simple: each player controls a squad of units with the aim being to eliminate all enemy units while maintaining at least one surviving unit. During their turn, a player can select one of their units and then move and attack with it.

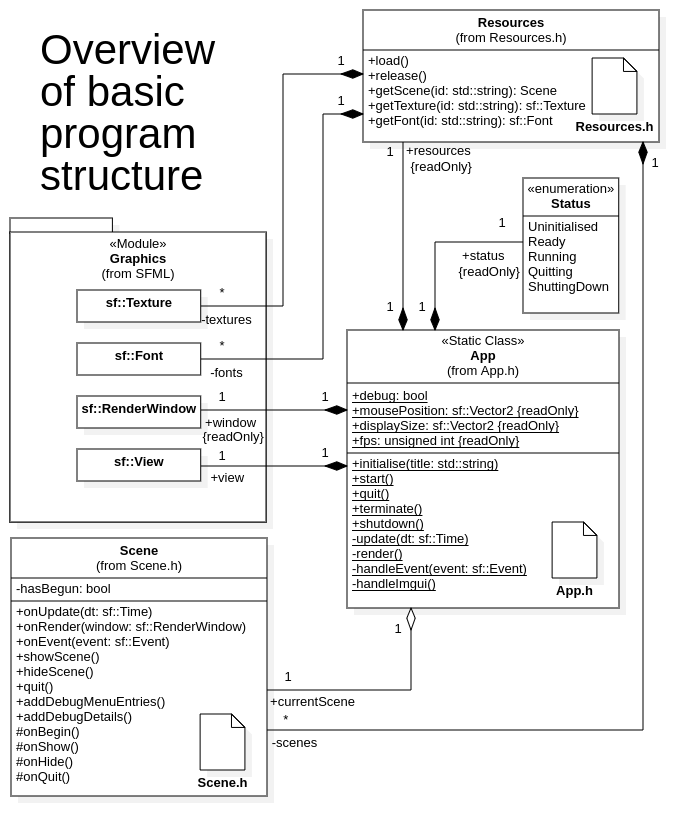

A screenshot, UML diagram and flowchart of the strategy game for this project.

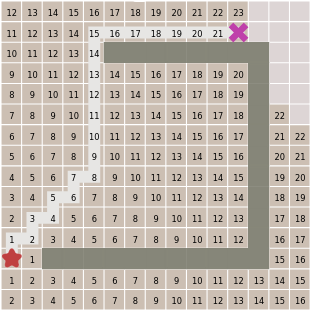

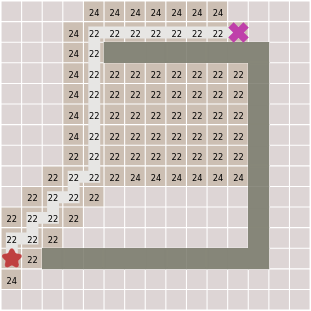

A player has a set amount of MP and AP (movement and action points) per turn, and can distribute them between each of their units. Each unit drains a different amount of MP per tile when moving and a different amount of AP when attacking as shown in the table below, meaning that some can move further and some can eliminate more units during a single turn. A unit can only attack another unit when it has enough AP and the target is in sight and range where nothing can be in between the attacker and their target.

| Unit | Description | MP Cost | AP cost | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melee | Fast close-range unit | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Blaster | Standard mid-range unit | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Sniper | Standard long-range unit | 2 | 2 | 10 |

| Laser | Slowest unit, longest range | 3 | 3 | 25 |

A table comparing the units used in the strategy game.

Resource management and positioning are the two key elements that make this game strategic. A player will have to distribute MP between their units to keep them out of the enemy’s range and line of sight while also positioning their units to attack the enemy safely. This won’t always be possible; the constraints of the MP and AP mechanics mean that sacrifices have to be made each turn in order to win.

Results summary

The investigation reached its conclusion. While it would be possible to create any number of AIs, it is believed that the research questions posed in the full thesis can be answered from the pool of AIs that have been created. Further AIs would have been created if the results had been more positive, but at this stage the creation of further AIs would simply provide more examples of problems already identified and not yield anything of benefit.

The prototype AIS used in this project are not the only examples of using A* for decision making — GOAP was actually used for the AI in the game F.E.A.R. There are significant differences between the approaches used in this investigation and GOAP; they are only related in the sense that they both use the A* algorithm, but there are clear distinctions between the implementations, usages and behaviours of their resulting AIs.

How plausible is it to use A* in a decision making process for game AI?

The existence of GOAP already demonstrates that A* can be used for AI purposes. However, the case studies suggest that A* is rather unsuitable for AI. One case study illustrated the most common flaw of reimplementing a search algorithm for AI: the AI has a tendency to do nothing unless it is told that doing nothing is wrong. This is problematic, as it should be valid for an AI to do nothing in the correct situation. This problem appeared in the creation of all case studies and the requirement for overcoming it introduces awkward and arbitrary elements to the AI. Telling the AI what not to do, as opposed to what it should do, makes both creating and changing behaviour difficult.

Another flaw in creating AI in this way is that it is hard to be certain about how the AI’s programming will affect behaviour. Every subsequent case study used different weighing functions, each having valid and constructive reasoning. However, in spite of the effort placed into designing these functions it can be concluded that the behaviour of each AI varies drastically and cannot be predicted from the programming alone. This aspect is unlikely to appeal to game developers, as there’s no way of knowing how the AI will behave or whether it is going to break in a given situation. With these things considered, the approaches created in this investigation have not produced any results showing signs of suitability and GOAP continues to be the most successful approach for applying A* to game AI.

How does the inclusion of pathfinding affect decision making?

GOAP’s Actions are used differently when compared to the Actions in this game: GOAP’s Actions are simple and only one instance is created for each type of Action whereas in this investigation an Action instance was created for every opportunity so that they could integrate with the pathfinding process instead of replacing it. Where GOAP’s AI would perform a single Move Action, the AIs observed in this study would have to perform a Move Action for moving to each tile when pathfinding. For GOAP, the choice to attack comes purely from the Attack Action, whereas in this study the AIs evaluated each possible Attack from each possible location. GOAP’s locations and targets are chosen based on the goals provided which reduces the number of Actions and States. In this study, the selections were made within the decision making process which had the opposite affect and inflated these numbers, having consequences in the performance and behaviour of A*.

Case three displayed promise for eliminating enemy teams intelligently. The AI had great gameplay strength and achieved a high aptitude for finding the best outcome of a situation. Feeding all possible situations to A* allows it to find the best sequence of Actions; when a heuristic is provided such as in case four, the algorithm has the ability to terminate early with an acceptable solution that isn’t necessarily the best. Cases three and four demonstrate that A* can make decisions such as where to move and who to attack when given a large number of options, but they also reveal the resulting impact on performance that makes these AIs unsuitable for more realistic applications.

In normal pathfinding on a grid, an agent using A* can move in four directions and the number of routes becomes manageable, but the AIs in this investigation can also attack, select a new unit and end their turn. This means that instead of 4 edges per node A* has to process roughly 10–20, greatly increasing the total number of nodes and the time to process a suitable sequence of Actions. Replacing the game with one that features less interactions would benefit the AI, but the game used in this experiment could already be considered a simplification when compared to commercial games and simplifying things further would not provide any insights applicable to most use cases.

How does changing the components used in A*s fundamental formula affect the output of the algorithm?

Case three relied entirely on the accumulation of Costs and used brute-force to repeatedly expand the cheapest nodes until the algorithm terminated, showing that a heuristic function wasn’t necessary for creating an AI as long as there was enough information reflected by the Cost. The introduction of a heuristic component with case four allowed for greater control over what the AI does but not necessarily how it does it — the heuristic function influenced the AI to eliminate an enemy unit or move closer if that wasn’t possible, making A* expand nodes more likely to satisfy this goal.

As soon as the goal was satisfied, the algorithm terminated meaning that case four would be suitable if there was another system to give it clear, achievable and specific goals to satisfy. Without goals, case four’s behaviour varied from doing nothing like in case one, to playing the game without any particular strengths or weaknesses.

How easy is it to externally influence the AI’s decisions or introduce difficulty?

This question is subjective and context dependent, as the complexity of influencing the AI is dependent on the fidelity of the task required of it and the notion of difficulty is dependent on the mechanics the AI can use to beat the player. For this investigation, the answer to the first part of this question can’t be answered with certainty. While case four managed to satisfy goals with relative ease, the designation of such goals is challenging in its own way. There had to be a guaranteed way of completing the goal in order for the algorithm to terminate successfully, creating the requirement of a valid goal.

Changing the difficulty of the AI was attempted in case study four when playing against case study three. Case study three won in the majority of situations, only losing when playing second in a long-range game against case four. The values for the penalties used in case four were changed, but no combination strengthened behaviour. If there was such a combination that achieved a higher level of strength, the process of finding it would be cumbersome, further reinforcing the lack of plausibility of this approach to game AI.

It could be speculated that the easiest way of introducing difficulty to the AI would be to select more effective goals; changing what the AI considers a goal is a somewhat simple way of changing how the AI plays, and case four already demonstrated how a weak goal resulted in weak behaviour. Alternatively, the implementation of the heuristic and weighing functions could be written with more complexity like the one in case three, although this would mean that each desired difficulty of AI would require alternative functions that then need to be tested independently for bugs.

Conclusions

Considering that the aim of using A* is to make the process of creating game AI flexible and modular, the methods used as a part of this research were unsuccessful in achieving the simplicity necessary to warrant their usage.

It was hypothesised that the combination of decision making and pathfinding would improve the communication of various systems and the output of the perception, decision and interaction processes. This hypothesis was proven false from the difficulties experienced in creating and observing these case studies as evidence, and therefore this project has failed to produce a suitable method of creating game AI using A*.

However, the project as a whole wasn’t a total failure. This research was performed because of the lack of knowledge in this area; GOAP is the only successful approach to have used A* for implementing decision making in game AI, and so this project investigated whether there were potential improvements to be made.

While no improvements were made, but it is hoped that this project leads to a greater understanding of the ways an AI can take advantage of the A* algorithm, or more specifically, how it cannot. The flaws found during the case studies of the full thesis brought attention to the reasons not to use A* for AI, but it is possible that there are benefits for using A* that couldn’t be identified in the scope of this project.

Thanks for reading! Be sure to check out the full thesis!