A link to the repository can be found here.

I wrote this post as I made the project, but to make things easier for newer readers I have been updating the codebase so that it takes advantage of some of the newer features of h-raylib and removes depreciated code. Check out the git repository for the latest updates and be careful when copy-pasting code — unless you’re running my repository or you’re using the exact same versions of libraries, some of this code may not work.

The biggest change was that I’ve manually implemented the first person camera, which has the added bonus of showing how we can handle input and make changes to our ECS world.

Previously on Apecs

Roughly 4 years ago, I wrote the post An introduction to game development to game development in Haskell using Apecs. I like to think it was one of my most well-received blog posts considering it is featured on the Apecs repository itself, as well as being a common topic across emails and communications I receive.

Apecs is a ‘fast Entity-Component-System library for game programming’ written in Haskell. It is by far one of the best ECS implementations I’ve used and also happens to be my favourite way of structuring games when using Haskell.

However, enough time has passed (4 years!) that some of the tricks and methods used in that blog post are old enough to confuse beginners. Since that was never my intention, I thought I’d make a new blog post about it!

About this post

This post is going to be a little bit different. Whereas normally I’d finish a project and write a post about it, in this post I want to write it as I go along! Each time I finish implement something substantial, I’m going to add to this post so that I can really capture more of the development process.

This may have a few side-effects, however. Firstly, code we write near the beginning may change towards the end. If I make a simple mistake (such as a syntax improvement), I’ll simply swap it out for the superior. But I want the big decisions I make to be written about so that if I later decide against it I can articulate properly why in the post.

My blog has support for both projects and blog posts; this post is a blog post since it is capturing a moment in time, like a photograph. The associated project for this page will be the formal write-up for how the game works, but this will act more as a portfolio piece than as a tutorial. This is a bit of an experiment for me, so please let me know how you think it goes!

Introduction

What is the ECS pattern?

As the name suggests, the ECS pattern is divided into three parts: entities, components and systems. These parts work together to form the foundations of your game’s architecture.

Entity — Alone, an entity is just a unique identifier, such as a simple integer value. They aren’t very useful by themselves!

Component — Data, essentially. Anything that has data you need to store between frames, such as position, velocity, health or gold. Each component is attached to an entity in some way — some games have just a big database where an entity is just an integer used as a look-up key, whereas others (who probably would be using object oriented programming) might compose component lists within the entity class itself.

System — The magic part that a lot of people miss out on! A system is simple: it iterates through entities and updates their components in some way. A player movement system might cherry-pick the player’s entity and update the velocity component with respect to whatever keys are held on the keyboard; a movement system would then iterate through all entities with positions and velocities and update their positions accordingly. If you can break the logic of your game into systems then things become a lot simpler and safer.

It was through ECS that I began to understand how modern game engines work (no thanks to you, university!) since having a greater appreciation for how games can be architected gave me an insight that couldn’t be taught through anything other experience. That isn’t to say that game engines all use ECS, in fact most of them don’t since they want to write their own systems (rendering, physics, scripting etc) that you then use and may or may not customise. Also, they probably don’t implement entities and components in the same way; both Unity and Unreal engines allow for logic to be placed in their components whereas the ECS pattern encourages components to be purely data.

What is Raylib?

One thing we haven’t mentioned yet is that this project will be using Raylib for the rendering side of things. I’ve always wanted to learn more about Raylib, and my chance came when I found the Haskell bindings released recently.

We won’t spend too much time talking about Raylib, in fact I’m using it purely because it’s a really easy way to get things on-screen. The documentation style surprises me a bit, with a preference for documenting the source code rather than an online version of the API. That said, for our purposes the cheatsheet is an excellent resource for just understanding what functions Raylib provides us with and what arguments they take.

What is Notakto?

Notakto is a variant of tic-tac-toe in which both players play using ‘crosses’ as their markers across multiple tic-tac-toe boards. Three crosses in a row on any board will ‘kill’ it, meaning that the board can no longer be played on. When there is only one board remaining, the player who kills it is considered the loser, meaning that to win you have to get yourself in a position where you force the other person to get three-in-a-row on the final board. It is still a solveable game like regular tic-tac-toe, but the stratagies involve enough effort that you will probably not find many people who can figure them out on their own.

Why did I chose to make Notakto? There’s a beauty in making a game where the rules are already well-defined since there is already a definition of ‘done’ — I know what I’m working towards and the project has scope, a perfect scenario for an experimental tutorial!

And with that, it’s 10:00 am, let’s begin our journey!

Getting started

Initial commit

I will be committing as I go, so even though this blog post may be revised for cleaner reading, the repository will always tell the full story. Each section will have a permalink to the commit I was at so that you can see how the project evolves. I won’t be detailing every single change in this blog post, so if you really are following along you may need to check the repository and fill the blanks in yourself.

A link to the repository’s first commit can be found here.

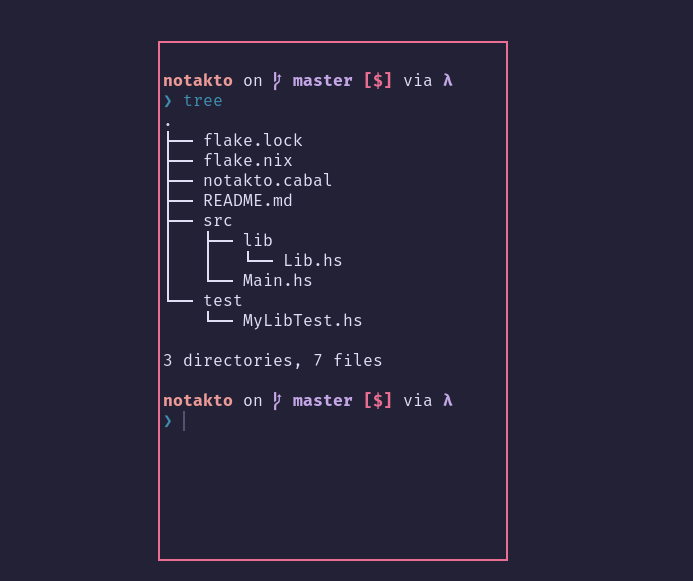

The folder structure of the initial commit.

Here we go! I’ve just pushed an initial commit with my standard Haskell bits and bobs. I always like making a library and separating executable-only code from the game itself, meaning that if we wanted multiple executables that handle the game setup in different ways (i.e. terminal or GUI) then we can. I’ve also got a testing folder, maybe we’ll write some tests as we go, who knows?

You may also notice that I am using Nix to build and run this project, so you should just be able to use nix run to run the project at any point in time. If you want to work in this repository, you can use nix develop to get your development environment set up.

At this point in time, running the project should print Hello, Notakto.

Introducing libraries

After setting up the repository, my next step with any project is adding the libraries I know I’ll be using and getting a modified example running to demonstrate that things are working correctly. Lets begin by updating our cabal file to include the h-raylib and apecs.

library

exposed-modules: Lib

hs-source-dirs: src/lib

build-depends:

base,

apecs,

h-raylib

default-language: Haskell2010Single file example

Imports, options and extensions

Now we can try and use our dependencies by modifying an example! Thankfully, h-raylib supplies us with a first-person-camera example, and I already have some Apecs examples from the project featured in my previous post!

{-# OPTIONS -Wall #-}

{-# LANGUAGE FlexibleInstances #-}

{-# LANGUAGE MultiParamTypeClasses #-}

{-# LANGUAGE TemplateHaskell #-}

{-# LANGUAGE TypeFamilies #-}

module Lib (main) where

import Control.Monad (unless)

import Apecs

import qualified Raylib as RL

import qualified Raylib.Colors as RL

import qualified Raylib.Constants as RL

import qualified Raylib.Types as RL

import Raylib.Types (Vector3 (..))Here is how our Lib module is setup now. We’re still working in one file to keep it simple, so it’s okay for things to be messy.

- I use the

-Walllanguage option just to make sure we’re ironing out warnings we go — personal prefence. - The language extensions you see are all used by Apecs (or at least, the example made use of them). I know for a fact that

TemplateHaskellis used as an easy way of building aWorldtype for use throughout the application. Libonly needs to exportmainfor now, but if we ever want to export a configuration data type that our client can provide then this is where we’d put it.- I try to structure my includes with my ‘Haskell libraries’ at the top (i.e. things that aren’t specific to my project), followed by blocks of imports for my dependencies:

- Apecs has quite a nice API; it doesn’t get messy if you just import it in its entirety and it almost feels like it’s part of the language.

- Raylib has a lot of things going on (again, refer to the cheatsheet, so I’ve

qualifiedit. Normally I’d explicitly write every function I use, however for this tutorial I’m going to use qualifications so that you can easily tell when something is a Raylib thing and when it’s something else.- I made an exception for

Raylib.Types— certain types are quite commonly used throughout the project and so rather than typingRL.Vector3constantly I instead explicitly imported it so that we can use it without restraint.

- I made an exception for

Creating and initialising a World

Next up is creating our World. In Apecs, the World is a type built specifically for your components to live in; that’s why TemplateHaskell is used to automatically write the code that glues your components together. The initWorld function is also a result of this template, which is why you might find it hard to find the World type and initWorld in the apecs documentation.

-- Define a component, a Camera

newtype Camera = Camera RL.Camera3D

-- Create a world featuring the lonely Camera component

makeWorldAndComponents "World" [''Camera]

-- Initialise our world in the main function, and give it to our game's systems

main :: IO ()

main = initWorld >>= runSystem (initialise >> run >> terminate)The big important function here is makeWorldAndComponents. In Apecs, there are multiple template-Haskell functions you can use to create your World and associated components:

makeWorldtakes your components and constructs yourWorldand component associations, but it doesn’t assume anything about your component’s storage mechanisms.makeWorldAndComponentscallsmakeWorld, but then also callsmakeMapComponentswhich takes all of your components and definesComponentinstances with aMapstore. In simple terms, it sets up your components with the most common storage mechanism,Map.

In this tutorial, I’ll be using makeWorldAndComponents to keep things simple, but if you ever want components that have specific constraints you might want to consider makeWorld and defining your mechanisms manually like I did in my previous post.

You probably want to use makeWorld if you want to be cool so that you have full control. Here’s how components would look if you want things to be done manually:

-- 'Map' storage: standard storage where any entity can have one

-- e.g. Every entity may have a name

newtype Name = Name String deriving Show

instance Component Name where type Storage Name = Map Name

-- 'Unique' storage: only one entity can have this component at maximum

-- e.g. Only zero or one entities can be marked as a player at any given time

data Player = Player

instance Component Player where type Storage Player = Unique Player

-- 'Global' storage: exactly one component exists for the lifetime of the game

-- e.g. There only needs to be one definition of the game's configuration

-- Note that querying for this on ANY entity will yield the global one,

-- effectively sharing the component between all entities

-- Also note that globals need instances for Monoid and Semigroup

data Config = Config String Int

instance Monoid Config where mempty = Config "Foo" 0

instance Semigroup Config where (<>) = mappend

instance Component Config where type Storage Config = Global ConfigSo even though I’m going to be lazy on this post so I can say ‘make a new component’, I really do encourage people reading this to try and use makeWorld instead.

For more information, check out the documentation and maybe even my previous post.

So, what are the initialise, run and terminate systems? Well, they are just functions with the type System World ()!

Systemis an Apecs type defining a system, one of the parts of the ECS pattern. Note thatSystem w ais mapped toSystemT w IO aunder the hood; it’s just a convenience type.Worldis our world type created by template haskell in the above snippet.()is the absence of type; we aren’t expecting these systems to return anything, so these particular functions are only for executing side effects.

Let’s first look at initialise:

-- Simple system, doesn't return anything

initialise :: System World ()

-- We're in the 'System' monad, use 'do' to compose side effects

initialise = do

-- Define a Raylib 3D perspective camera and name it 'camera'

let camera = RL.Camera3D (Vector3 0 1 0) (Vector3 2 1 1) (Vector3 0 1 0) 70

RL.cameraProjection'perspective

-- Create a global entity with our camera component

-- 'set' is an apecs function for setting a component's state on a given entity

-- 'global' refers to the singular and unique global entity of the game

-- 'Camera' refers to the constructor for our component which contains a RL.3DCamera

set global $ Camera camera

-- The 'System' monad has IO, remember 'System w a = SystemT w IO a'!

liftIO $ do

-- Now we can compose side effects for IO, which is what h-raylib uses

RL.initWindow 1920 1080 "App"

RL.setTargetFPS 60

RL.setCameraMode camera RL.cameraMode'firstPersonThe biggest takeaway from the above snippet is to remember that just because we’re in Apecs-land doesn’t mean that we’re constrained to only using Apecs functions. System is a type constructor for SystemT, which apecs documentation explains:

A

SystemTis a newtype aroundReaderT w m a, wherewis the game world variable. Systems serve to:

- Allow type-based lookup of a component’s store through

getStore.- Lift side effects into their host Monad.

We can do IO 🎉 Before we continue though, let’s look into terminate, since it’s good practice to always write in programming to always write delete where there’s new, or a destructor whenever you write a constructor. We have made our window, so let’s handle closing it before we forget:

-- When terminate is called, just close the window

terminate :: System World ()

terminate = liftIO RL.closeWindowThis is a short and sweet one!

The question on your mind might be “why did we need to do this in a System?” The answer to that lies in the names: initialise and terminate. Yes, the Raylib specific stuff could be done purely in IO without Apecs getting involved, but this is constraining.

What if we want to store the want to load and save data using a file when the application opens and closes? What if we need to correct the state of the game before we enter the game loop, or after it’s concluded? So long as we’re in a System, we have access to all the components in the World; exiting back into IO removes this ability and so I prefer to use liftIO within System to get the best of both worlds.

Updating and rendering

We aren’t quite done with our single-file example since we have one remaining undefined function: run. Let’s dive in:

run :: System World ()

run = do

update

render

shouldClose <- liftIO RL.windowShouldClose

unless shouldClose runHang on a moment, this is a game loop! So in main, we had initialise >> run >> terminate, you can now see that the reason the program doesn’t terminate immediately is because run is hogging the thread and infinitely looping until told otherwise!

So what are update and render? Well, when you are in a monad be it IO or System, you can easily call functions of the same monadic type to compose side effects. You could pretty much substitute update and render for their contents and everything will work the same; this is a way of breaking things up. I like updating the game and then rendering the result. We can split these two steps into as many more steps as we need, but for our single file example they are singular systems that just handle the entire game.

-- Simple system

update :: System World ()

update = do

-- Retrieve the camera component from the global entity (c is a RL.Camera3D)

Camera c <- get global

-- Update the camera and store the updated version in c'

-- Also note the use of liftIO to dip into the IO monad to allow the use of raylib

c' <- liftIO $ RL.updateCamera c

-- Replace the global entity's Camera with a new one containing the updated camera

set global $ Camera c'I was a bit alarmed at first at how small this function is — where is the input handling? Where’s the movement speed definitions and all the other things we expect to see in a first-person game? Well it looks like Raylib is has some very plug-and-play style functions, which is nice to see when playing around. I’m sure anyone looking to make an FPS will be able to roll their own movement system, but for us we’ll be removing this pretty quickly since funnily enough Notakto is not a competitor to Call of Duty.

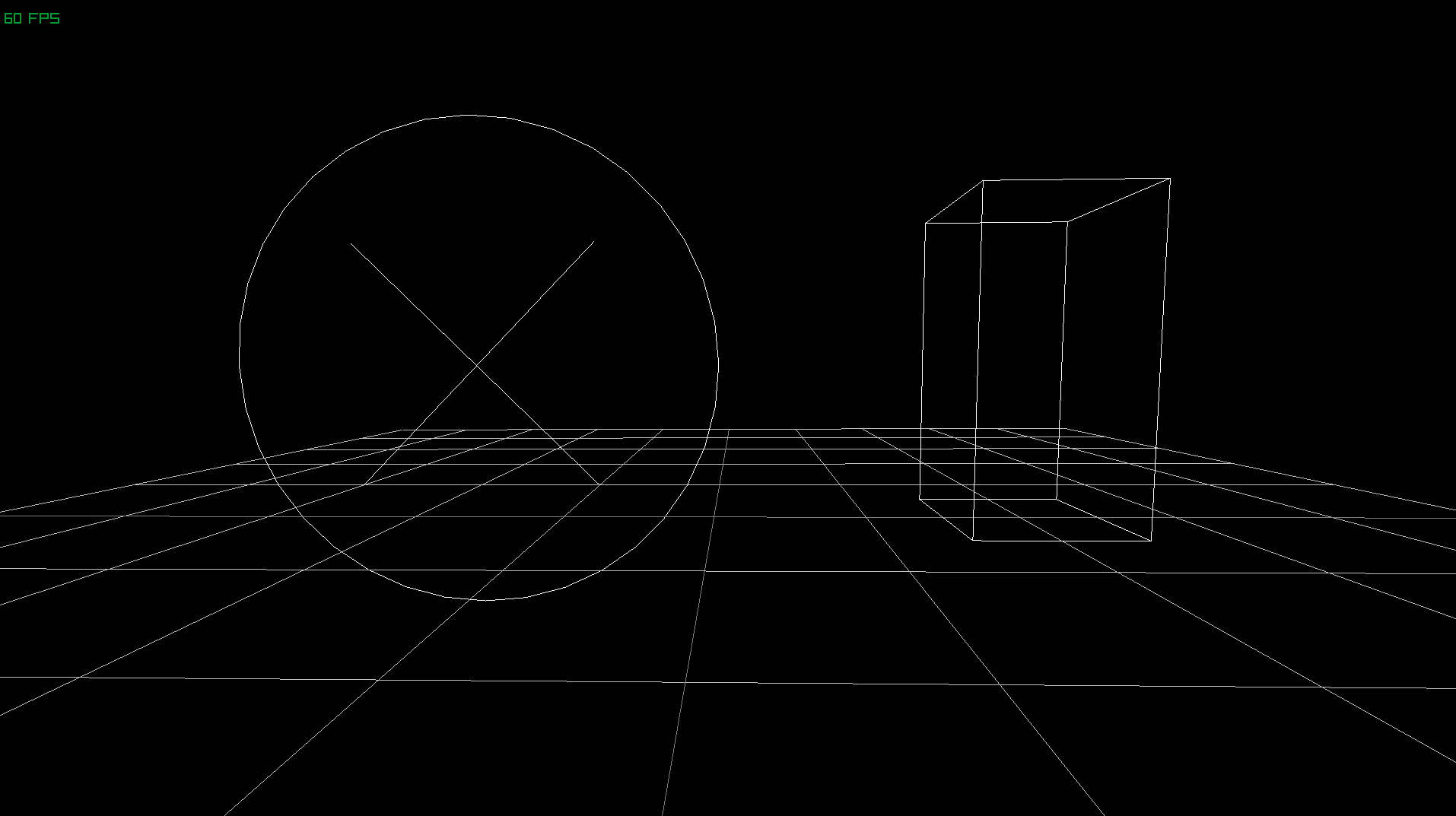

render :: System World ()

render = do

Camera camera <- get global

liftIO $ do

RL.beginDrawing

RL.clearBackground RL.black

RL.drawFPS 10 20

RL.beginMode3D camera

RL.drawGrid 10 1

RL.drawCircle3D (Vector3 2 1 1) 2 (Vector3 0 1 0) 0 RL.white

RL.drawLine3D (Vector3 3 0 1) (Vector3 1 2 1) RL.white

RL.drawLine3D (Vector3 3 2 1) (Vector3 1 0 1) RL.white

RL.drawCubeWiresV (Vector3 (-2) 1 0) (Vector3 1 2 1) RL.white

RL.endMode3D

RL.endDrawingThe render system is very straightforward. We grab our camera out of our Apecs World and then use it in the IO monad to help Raylib render the world. I won’t go into much detail here.

After what feels like an eternity (it has taken me 2 hours to write this!), here’s our single file example up and running! Time for a toilet break and a glass of water!

Screenshot of the single file example running.

A link to the corresponding commit for the previous section can be found here.

Visualising the state of the game

What should be an entity?

I believe that the next step of this project is to visualise the boards and the marks placed upon them. In terms of priority, I want to get the visuals set up first otherwise testing the game is going to be a pain, but in order to get that done we need to create a basic representation of state!

So, representations of state — data types! Let’s make some new types to represent things we’ll need in our game! But wait.. Do you hear alarm bells?

While it’s all fun and games to get experimental and start playing around with Haskell’s wonderful type system, sometimes we can get bogged down in actually using these types and trying to make them work.

Let’s take a moment to appreciate the blank slate we have right now and come up with at least a hypothesis for how things should be laid out.

After heeding that warning, let’s create an action plan. What should consist of an entity in our game? More specifically, should the boards themselves be entities? Should the marks that players place be entities? One could argue that both the board itself and the crosses placed could be entities. I disagree; I believe that the crosses don’t really make sense without the context of a board, and so there’d be little use in having an entity representing each cross in isolation (it might even make things more confusing trying to figure out which board each cross is on).

| Thing | Is Entity? | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| Player | Maybe | The player won’t have much data of their own; they can be represented elsewhere. If it turns out we want things like customisable player names and colours then they could become entities. |

| ‘Game’ | Global | The global entity can contain a component with the information for who’s turn it is (either player one or player two). |

| Cross | No | Crosses don’t have much of their own data other than their location, which is dependent on the board. Standard Haskell data types will suffice. If they were their own entity, we could potentially have more than nine crosses assigned to a signle board. |

| Board | Yes | Boards contain the state of crosses placed on them, as well as whether they are ‘dead’ or not. Their state will need to be rendered. |

A table describing my plan for entities in Notakto.

I believe that’s all we need to think about to get started; let’s do some programming.

The Types module

A single-file example is nice, but is only going to impede us going forward; let’s make a new module containing all of our components and miscellaneous types: Types.hs!

{-# OPTIONS -Wall #-}

{-# LANGUAGE FlexibleInstances #-}

{-# LANGUAGE MultiParamTypeClasses #-}

{-# LANGUAGE TemplateHaskell #-}

{-# LANGUAGE TypeFamilies #-}

module Types (

World,

initWorld,

Camera (..),

) where

import Apecs

import qualified Raylib.Types as RL

newtype Camera = Camera RL.Camera3D

makeWorldAndComponents "World" [''Camera]So I’ve moved all language extensions into this new file, since they’re only relevant for the World initialisation code. We now have a cleaner space to declare new data types, and since components should be simple, we should be fine to place them all in here for the duration of this project.

The BoardComponent

In the previous section, we asked the question “what should be an entity?” Now that we know of some certain entities, we now need to think about what components we might like to attach. The one I’m most interested in right now is a representation of a board, the standard tic-tac-toe battle ground.

-----------

-- Types --

-----------

data Cell = Empty | Filled deriving (Show, Eq)

----------------

-- Components --

----------------

newtype CameraComponent = Camera RL.Camera3D

data BoardComponent = Board {

_tl :: Cell, _tc :: Cell, _tr :: Cell,

_ml :: Cell, _mc :: Cell, _mr :: Cell,

_bl :: Cell, _bc :: Cell, _br :: Cell

} deriving (Show, Eq)

makeWorldAndComponents "World" [''CameraComponent, ''BoardComponent]This will do for now I think, no need to get too fancy. One thing I’d like to draw your attention to is the separation of standard types and types that are used as components — components are the things you’ll be operating on when using Apecs, so try to organise your code in a way which makes sense to you. I’ve appended Component to my component types, but I’ve omitted it from my data constructors so I don’t have to type it out as much.

Now go back to Lib.hs and fix any errors we have and ensure things still run. Let’s also create an entity with BoardComponents to represent a singular board while we’re at it!

initialise :: System World ()

initialise = do

-- Update location of camera so we can look at origin

let camera = RL.Camera3D (Vector3 0 1 6) (Vector3 0 1 0) (Vector3 0 1 0) 90

RL.cameraProjection'perspective

-- Define what a blank board looks like

newBoard = Board Empty Empty Empty Empty Empty Empty Empty Empty Empty

set global $ Camera camera

-- Create a new entity with a blank board

-- Note: if you want the return value, omit '_'

newEntity_ newBoard

liftIO $ do

RL.initWindow 1920 1080 "App"

RL.setTargetFPS 60

RL.setCameraMode camera RL.cameraMode'firstPersonRendering

Now that we have some data floating around cyberspace it’s time to prove that we do indeed have some state by trying to visualise it. Now for the sake of fun, I’m going to continue to use the first-person camera. If this was any other project I’d throw it out the window, but it gives us an event handling system built as well as a great opportunity to experience Notakto in 3D! Throwing it away right now would just create a detour since we can use it in the short term to explore our world.

If you’re planning to use this project as a springboard for a 2D project, you might be thinking of splintering off here and doing some exploration with Raylib’s 2D camera. I have to say that it doesn’t look too scary, so maybe this would be a good point for you to take a break and play around with it. We will be using cubes and 3D shapes to represent our boards in 3D space, so you’ll have to translate things as you go. If you want to continue using 3D, I’m sure it wouldn’t take long to switch it out for 2D later down the line.

If you choose to split off now, good luck!

Once again, I’m going to make a new module: Rendering.hs. This module is going to import Types and be imported by our main Lib module. This module will house all the dirty Raylib rendering things so that our main file can be more gameplay-focused. I’ve also moved the render function into this module so that we only have to export a single function for the entire module.

module Rendering (

render

) where

import Apecs

import qualified Raylib as RL

import qualified Raylib.Colors as RL

import qualified Raylib.Constants as RL

import qualified Raylib.Types as RL

import Raylib.Types (Vector3 (..))

import Types

render :: System World ()

render = do

Camera camera <- get global

liftIO $ do

RL.beginDrawing

RL.clearBackground RL.black

RL.drawFPS 10 20

RL.beginMode3D camera

RL.drawGrid 10 1

-- Our systems are sandwiched between the 'begin' and 'end' functions

renderBoards

liftIO $ do

RL.endMode3D

RL.endDrawing

renderBoards :: System World ()

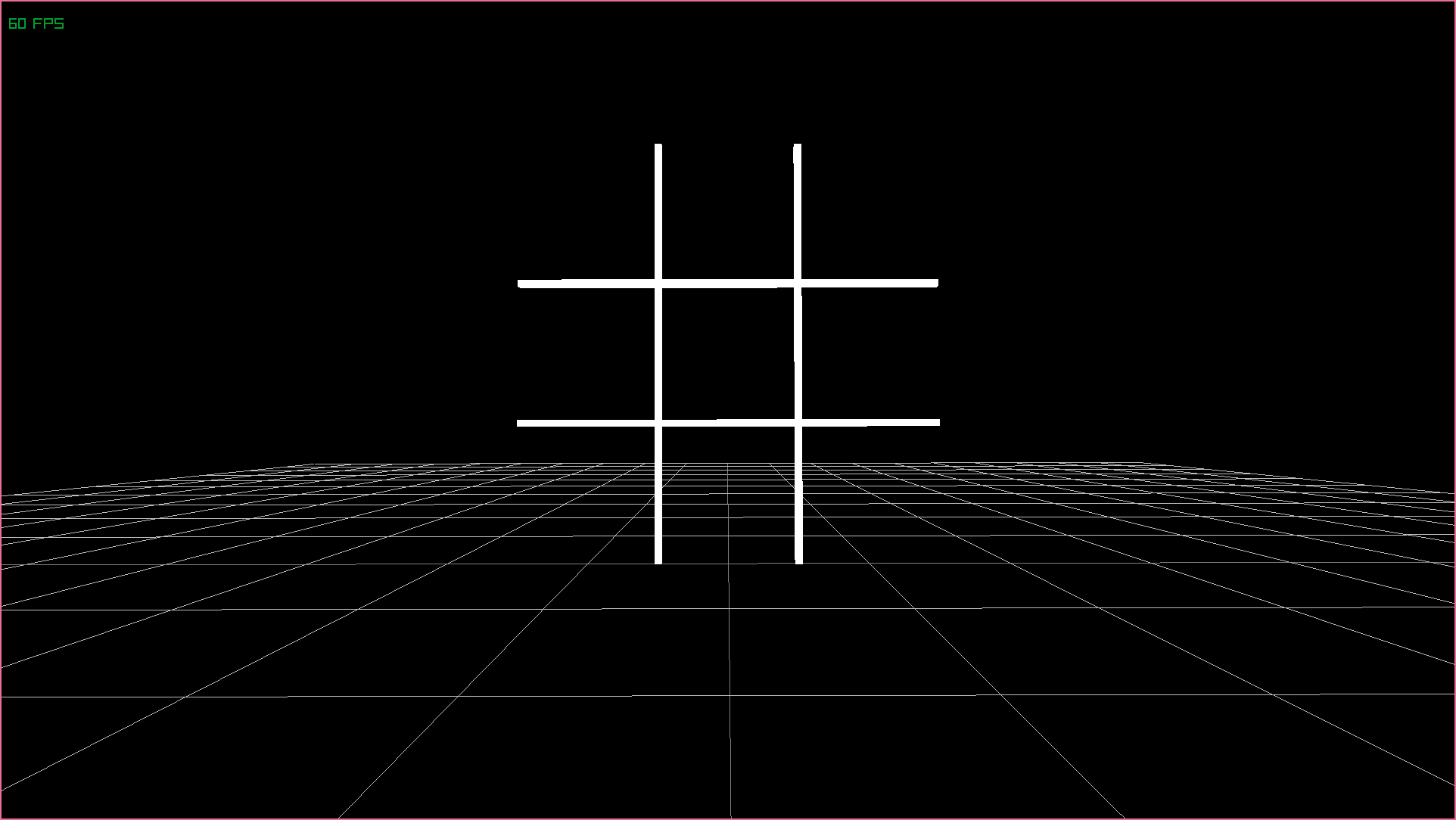

renderBoards = undefinedTime to get creative! We need to draw some array of cubes and shapes to visualise the board! Our use of RL.drawGrid means we can visualise the units of the world — the grid is spaced such that each cell is 1 unit by 1 unit. Now we just need to draw 4 cuboids to mock out a hash symbol.

-- Those experienced with monads can probably guess what cmapM_ does

renderBoards :: System World ()

renderBoards = cmapM_ renderBoard

-- The signature of this function also qualifies as a condition, only the

-- entities that satisfy said condition will have this function mapped onto them

-- In short, only entities with a BoardComponent get rendered via this function

renderBoard :: BoardComponent -> System World ()

renderBoard b = liftIO $ do

RL.drawCube (Vector3 0.5 1.5 0) t 3 t RL.white

RL.drawCube (Vector3 (-0.5) 1.5 0) t 3 t RL.white

RL.drawCube (Vector3 0 1 0) 3 t t RL.white

RL.drawCube (Vector3 0 2 0) 3 t t RL.white

-- 't' is the thickness here

where t = 0.05The key takeaway here is cmapM_. Let’s quickly recap the other variants so that we can deduce what this does (I’m going to shorten the type signatures a bit here):

cmap :: (cx -> cy) -> System w ()

This function maps a standard, non-monadic function onto all entities with cx. What is cx you might ask? Well I shortened the type signature for the blog (sorry) but it’s a polymorphic parameter representing a bundle of components. Apecs leverages Haskell’s type system to intelligently select all entities that meet the criteria for cx. A singular type is one of the simplest forms of using this function; notice how our renderBoard function requires a parameter of BoardComponent. We can actually specify more than just a single component, and Apecs will use that group as cx. Similarly, cy is a group of components to be output.

cmapM :: (cx -> System w cy) -> System w ()

This function is very similar to cmap with one exception — the function mapped onto entities returns a composable side-effect of the System monad, which also means access to IO as well as other Apecs functions. You will typically use pure <your components> to return things. Appending M to a function to denote the presence of a monad is very common in Haskell.

cmapM_ :: (cx -> System w ()) -> System w ()

Once again, very similar, except this time to cmapM. We still have access to monads, except the function we map onto entities no longer produces a cy. This means that the function you’re mapping onto your entities is there to only produce side-effects. In the case of renderBoards, we want to map a monad function to our entities, but we don’t need to return anything, so cmapM_ is used.

After all of that, we have our first board rendered!

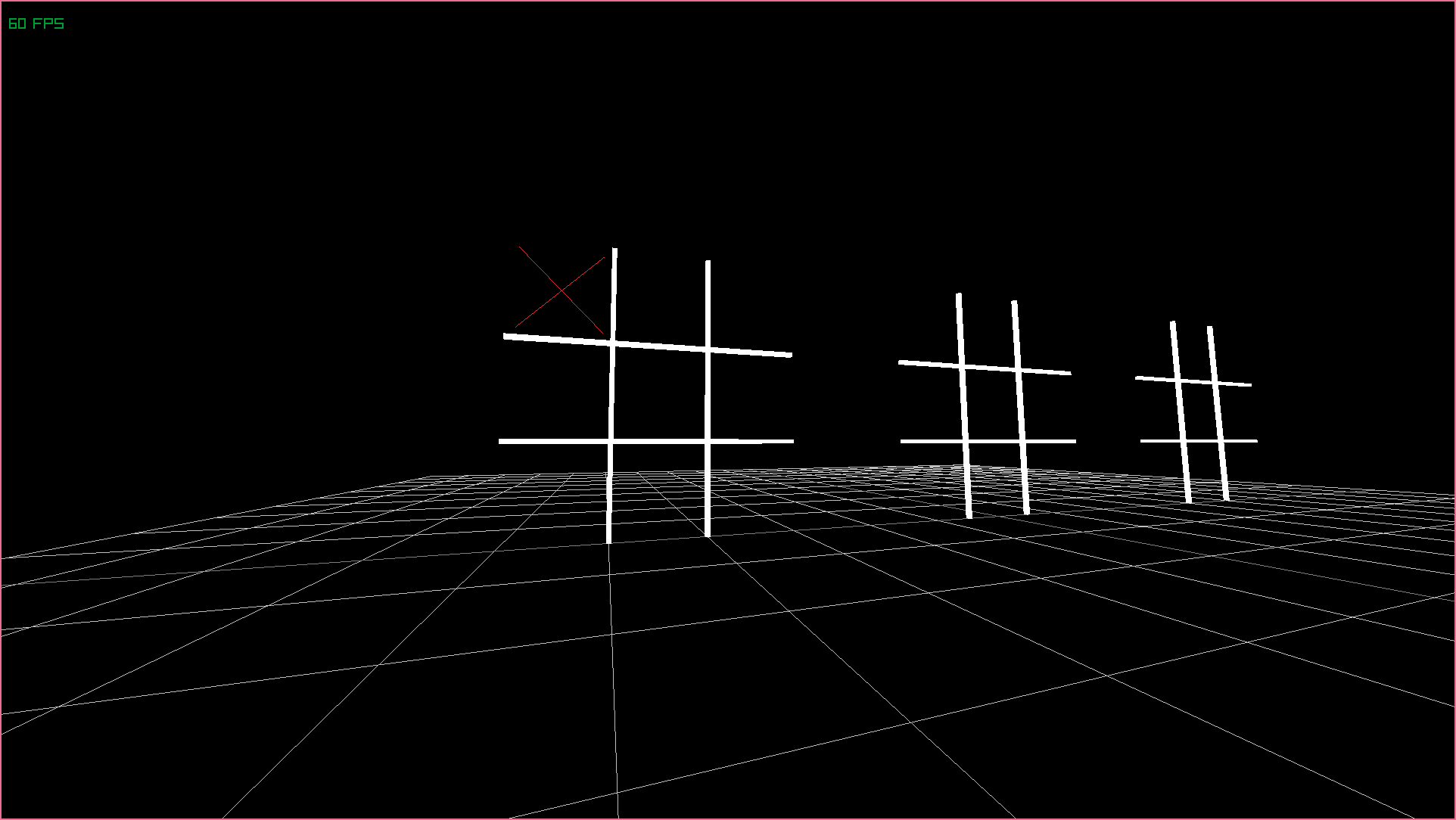

Screenshot of our first board being rendered in 3D space.

What does this tell us? Well, if we had no entities in the game that contained a BoardComponent, this arrangement of sticks wouldn’t appear in the world at all! We have correctly defined, initialised, stored, read and visualised state, even on a very basic level!

There are some things however that this doesn’t tell us:

- It won’t tell us how many boards there are, they all render on top of each other.

- It won’t show us the state of the board, since we aren’t rendering crosses yet.

- It won’t help us realise why we should love the game of Notakto.

Multiple boards

Let’s address this issue of not being able to see multiple boards. There’s two ways I can think of for going about this:

- We could create a new component representing the origin of the board in 3D space.

- We could count the number of boards and distribute them evenly along the x-axis.

Honestly, we’ll probably end up doing option one eventually, but because I like the idea of boards being automatically arranged I’m going to go with option 2 for now. I think the end game is a mixture of both approaches, where we automatically generate positions for each board, for instance in a circle or something.

renderBoards :: System World ()

renderBoards = do

-- Now we count how many entities have a BoardComponent using cfold

numBoards <- cfold (\c (Board{}) -> c + 1) 0

-- We provide the count to renderBoard

-- Also, we want to FOLD now, since we're iterating through boards

cfoldM_ (renderBoard numBoards) 0

-- We now know the total number of boards as well as the current board

renderBoard :: Int -> Int -> BoardComponent -> System World Int

renderBoard total i b = liftIO $ do

-- Each of our cubes are now offset using a function we define below

RL.drawCube (addVectors origin $ Vector3 0.5 0 0) t 3 t RL.white

RL.drawCube (addVectors origin $ Vector3 (-0.5) 0 0) t 3 t RL.white

RL.drawCube (addVectors origin $ Vector3 0 0.5 0) 3 t t RL.white

RL.drawCube (addVectors origin $ Vector3 0 (-0.5) 0) 3 t t RL.white

-- Return the next index (so we can track progress through iteration)

pure $ i + 1

-- Determine the origin of the board (4.5 = length of board (3) + padding (1.5))

where offset = fromIntegral (total - 1) * 0.5

origin = Vector3 (CFloat (fromIntegral i - offset) * 4.5) 1.5 0

-- Convenience function for adding a vector to the origin, used above

offset p = addVectors p $ Vector3 (CFloat origin) 0 0

t = 0.05

-- Raylib bindings need love; we need to make a function for adding vectors

addVectors :: Vector3 -> Vector3 -> Vector3

addVectors a b = Vector3

(vector3'x a + vector3'x b)

(vector3'y a + vector3'y b)

(vector3'z a + vector3'z b)The biggest change we’ve made here is the use of cfold and cfoldM_. Our first use of cfold is given a pure function that doesn’t use monads, therefore we use cfold. The second one does use monads, and since we don’t care about a return value we use cfoldM_. Folding is a generic way of doing things like accumulation or filtering; you iterate through the list as well as another parameter, be it a ‘count’, ‘total’ or an entirely different list. In this case, we used folds to firstly count the number of entities satisfying a condition (whether they had a BoardComponent), then we used another fold to iterate through the same set of entities, except this time we used the iteration value (index) as a way of knowing how far through we are, kind of like a for loop in imperative languages.

An entity is just a wrapper for an integer value; in theory you could just use the entity’s ID itself to work out where the boards need to go. However, this will become problematic if you initialise other entities before or in the middle of your boards, as now your boards’ IDs won’t be sequential in the way you expect!

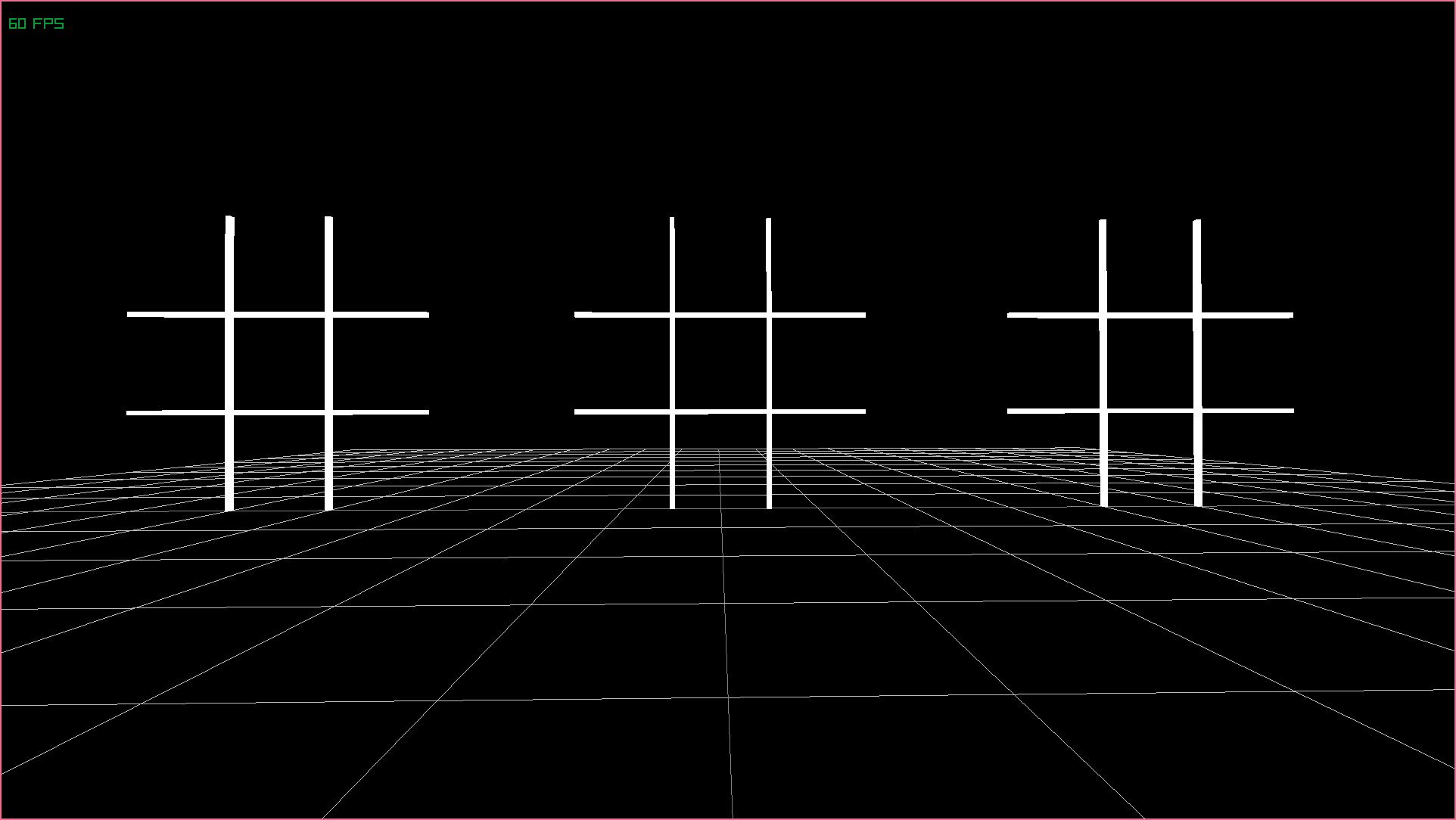

With that out of the way, let’s instantiate more entities!

-- Let's make 3 boards!

newEntity_ newBoard

newEntity_ newBoard

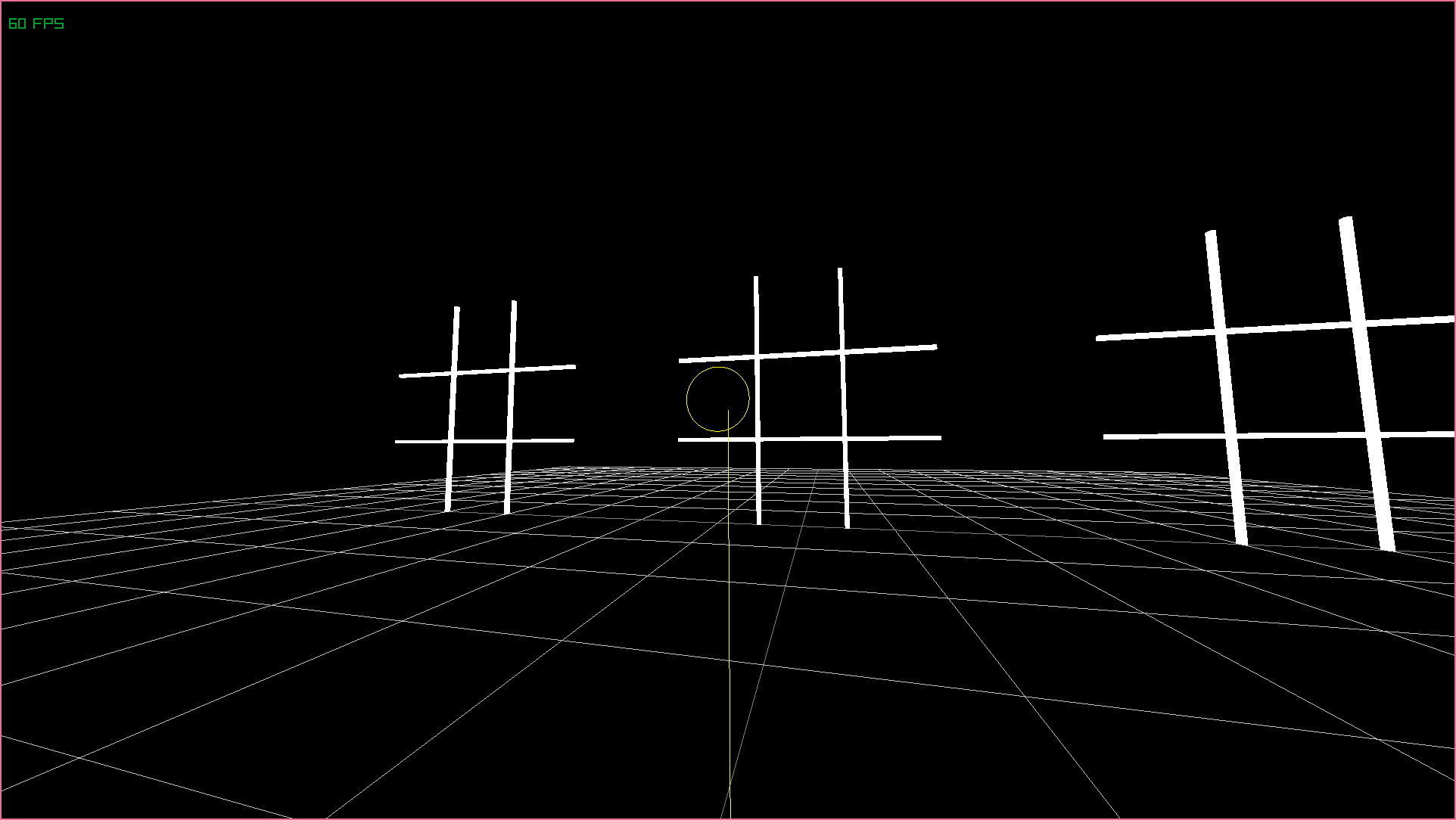

newEntity_ newBoardObjective complete! Even though the components of each of these boards have the exact same state, the fact that there are multiple entities now reveals itself visually!

Now we can render as many boards as we like, distributed along the x-axis.

Board state

Time for the final piece of the puzzle: rendering a representation of what marks have been placed on each board! We’re almost there, I promise. This is more of the same kind of stuff.

renderBoard :: Int -> Int -> BoardComponent -> System World Int

renderBoard total i b = do

-- Render crosses as part of renderBoard

-- We provide the origin value as well as the component

renderCrosses origin b

liftIO $ do

RL.drawCube (addVectors origin $ Vector3 0.5 0 0) t 3 t RL.white

-- <...>

-- Given an origin, render a cross for each cell

renderCrosses :: Vector3 -> BoardComponent -> System World ()

renderCrosses origin b = do

-- This function's job is to geometrically define what 'top left' etc means

renderCross origin (-1) 1 (_tl b)

renderCross origin 0 1 (_tc b)

renderCross origin 1 1 (_tr b)

renderCross origin (-1) 0 (_ml b)

renderCross origin 0 0 (_mc b)

renderCross origin 1 0 (_mr b)

renderCross origin (-1) (-1) (_bl b)

renderCross origin 0 (-1) (_bc b)

renderCross origin 1 (-1) (_br b)

-- Now we have an origin as well as a horizontal + vertical offset and a cell

renderCross :: Vector3 -> Float -> Float -> Cell -> System World ()

-- If the cell is empty, we just do nothing (pure nothingness, pretty metal!)

renderCross _ _ _ Empty = pure ()

-- If the cell is filled, we render a cross

renderCross origin i j Filled = liftIO $ do

-- We simply draw 2 lines, bottom left to top right...

RL.drawLine3D (f (-0.4) (-0.4)) (f 0.4 0.4) RL.red

-- ... and then bottom right to top left

RL.drawLine3D (f 0.4 (-0.4)) (f (-0.4) 0.4) RL.red

-- We have some helper values here, center being the center of the cell

-- calculated using the origin and offsets

where center = addVectors origin $ Vector3 (CFloat i) (CFloat j) 0

-- As well as a helper function to create start and end points

f x y = addVectors center $ Vector3 x y 0Ready to test it out? Let’s ammend our initialisation for one of the boards:

newEntity_ $ Board

Filled Empty Empty

Empty Empty Empty

Empty Empty Empty

newEntity_ newBoard

newEntity_ newBoardAnd now we see that the first board has the top-left cell filled! We can now visualise both the amount of boards and the content of each one! Chapter over!

We can now visualise the state of each board.

A link to the corresponding commit for the previous section can be found here.

Making moves

Preparing the raycast

Okay, it’s time to speed up and do some gameplay code. In order to make moves, players will need to shoot a ray out from the camera into the boards so that they can precisely specify where they want to place their cross. Let’s start by adding a new component responsible for storing the player’s current aim. We don’t have to give it a default value as it’ll be written during our update frame anyway.

-- New component to add (Types.hs) and add to World

newtype PlayerAimComponent = Aim RL.Ray

-- New update system to add (Lib.hs) and be called from update system

handlePlayerAim :: System World ()

handlePlayerAim = do

-- Determine window size so that we can cast from center of screen

windowWidth <- liftIO RL.getScreenWidth

windowHeight <- liftIO RL.getScreenHeight

- Retrieve the camera (will have just been updated)

Camera camera <- get global

-- Create a ray to be cast later

ray <- liftIO $ RL.getMouseRay (RL.Vector2

(CFloat $ fromIntegral windowWidth / 2)

(CFloat $ fromIntegral windowHeight / 2)) camera

set global $ Aim ray

-- New render system to add (Rendering.hs) and be called from render system

renderAimRay :: System World ()

renderAimRay = do

-- Retrieve player aim component

Aim ray <- get global

-- Determine endpoints of a line to draw

-- Note that we slightly offset the start location since we are drawing

-- from the camera, and if we didn't offset then the line would appear

-- as a dot!

let lineStart = addVectors (RL.ray'position ray) (Vector3 0 (-0.05) 0)

lineEnd = addVectors (RL.ray'position ray) $

multiplyVector (RL.ray'direction ray) 10

-- Render the line

liftIO $ RL.drawLine3D lineStart lineEnd RL.yellow

-- New utility function

multiplyVector :: Vector3 -> Float -> Vector3

multiplyVector a b = let b' = CFloat b in Vector3

(vector3'x a * b')

(vector3'y a * b')

(vector3'z a * b')We have momentum now! We haven’t done anything gameplay related really yet, but we’re blasting through the basics and now we’re ready to try and cherry-pick a cell from a board. This yellow line will be really helpful for making sure that the selected cell we’re going to calculate is in the approximate area of the ray.

This is where having each cross as its own entity has a benefit; each cross could easily check if it the raycast strikes it and our picking system would be done in a matter of minutes. However, the drawbacks of this is the task of connecting it back to the board and making changes to the game state. Instead, we’re going to see if the raycast collides with the board, and use the position it strikes the board to determine which cell the player is aiming at.

A link to the corresponding commit for the previous section can be found here.

Identifying the looked-at cell

I knew it was coming; the problem with writing the blog post as I go means that I get stuff wrong. I initially thought it would be a good idea to simply count the entities and render the board in a position dependent on it’s index, however this is just going to be so annoying to calculate each time. That’s okay though, as both Haskell and Apecs are really easy to experiment with and try new things. Here’s a quick correction to our project:

-- New component for tracking positions in 3D space

newtype PositionComponent = Position RL.Vector3 deriving (Show, Eq)

-- Initialisation system for automatically creating n boards across the x axis

-- Note: Thanks to our position component, you could create all sorts of patterns!

createBoards :: Int -> System World ()

createBoards n = do

-- forM_ is standard library, it's equivalent to flip mapM

-- Also notice that to create an entity with multiple components we use a tuple

forM_ positions $ \p -> newEntity_ (newBoard, Position p)

where newBoard = Board Empty Empty Empty Empty Empty Empty Empty Empty Empty

-- List comprehension to dynamically generate a list of x coordinates

positions = [Vector3 x' 1.5 0 | x <- [0..n - 1],

let x' = (fromIntegral x - (fromIntegral (n - 1) / 2)) * 4.5]

-- Forget cfoldM_, we're back to cmapM_

renderBoards :: System World ()

renderBoards = cmapM_ renderBoard

-- Notice the tuple - this is how you select entities that contain both components

-- Note: You can use the 'Not' type to ensure the entity DOES NOT have that type

renderBoard :: (BoardComponent, PositionComponent) -> System World ()

renderBoard (b, Position p) = do

renderCrosses p b

liftIO $ do

RL.drawCube (addVectors p $ Vector3 0.5 0 0) t 3 t RL.white

RL.drawCube (addVectors p $ Vector3 (-0.5) 0 0) t 3 t RL.white

RL.drawCube (addVectors p $ Vector3 0 0.5 0) 3 t t RL.white

RL.drawCube (addVectors p $ Vector3 0 (-0.5) 0) 3 t t RL.white

where t = 0.05This is where things get tricky… I’ve actually had to file a bug report since the raycasting and collision of Raylib don’t seem to be working great. It seems that data that we’re receiving isn’t what we expect and is slightly unreliable unless we do some IO before accessing it. Raylib wasn’t written in Haskell, and so even though our programming can easily be reasoned about, there’s a bit of a grey area where bindings to libraries written in other languages are. For now though, I’m just going to pretend the bug doesn’t exist and try to implement more of the program.

Before we continue, we need to ask ourselves what we actually want to do. Right now, my goal is to make it so that when you aim at a cell, we see a ‘ghost’ of a cross that will appear if you hit the left mouse button. The biggest question is, how do we want to store this bit of state?

- We could change our

Celltype to be eitherEmpty | Filled | Chosen, however that will require us to make sure that only one cell is chosen at most, which is more work. - We could specify a new variable on the

BoardComponentto keep track on which cell is chosen, but that would mean that we could have multiple chosen cells across multiple boards. - We could update the

PlayerAimComponentto contain both the ray and the looked-at cell — while this would work, it would be assuming that we’re only interested in players looking at cells, and wouldn’t be very good if your game had multiple things players could interact with. - We could try to avoid writing state altogether, but this would mean that every cell will need to crunch the numbers to work out if you’re looking at it every rendering loop. This would also mean that we have to test cells in isolation, meaning that there could be a situation where you’re technically looking at multiple cells at once.

Isn’t gamedev fun? I believe that I’m going to go for option 3. Note that if you were doing a look-at system in a different type of game, you’d most likely just record which Entity you’re looking at. The only reason we are in this scenario is because we avoided making crosses be their own Entity.

If you are looking to improve yourself as a programmer it’s always a good idea to think about all the different ways you could solve a problem before you get started. You (or your team) could begin to spot glaring issues before they manifest, and they also reassure you that if things go wrong you have other ways of solving things. Of course, don’t spend ages planning as you can’t always capture every potential problem without giving things a go.

If you’re struggling with thinking of approaches (and believe me, there are always better ways of writing things and numerous things that could be improved), try some of the following methods:

Start making a list — Sometimes, by simply writing ‘1.’ and arranging your thoughts into a list, you naturally start thinking of new entries to pad it out. I literally did this in the section above! Give yourself a space to prove to yourself you can do this!

Take your initial approach and make small adjustments — Sometimes you can quickly create alternative approaches by simply taking your first idea and altering it slightly; option 2 could be the same as option 1 with an addition or exception. For example, if your idea was to add a new variable to something, maybe consider if it could also be added somewhere else or added in a different way such that it has multiple uses.

Pretend to be a super-villain — Let’s say that it’s become your job to sabotage your code in some way, whether that’s by misusing the code or using the application in unintended ways. What would you do, and what kinds of things could you break? Now come back to reality and think about the likelihood of any of those scenarios, the risks they present and the cost of prevention.

Consider not doing it — Lack of action is itself an action, and so questionning whether you need to implement your feature in the first place isn’t a bad question to ask. Sometimes it exposes how many drawbacks there are versus the benefits, and perhaps what you might consider a workaround turns into one of your alternative approaches. What is the requirement that is driving this decision? If there isn’t one, then maybe we need to understand our requirements first.

Huzzah, after a few days that bug was fixed! Let’s get on with approach number three:

-- New data type representing the player's current looked-at cell

data LookAtTarget = NoTarget | Target Entity Int deriving (Show, Eq)

-- Update the aim component to make use of our new type

data PlayerAimComponent = Aim RL.Ray LookAtTarget deriving (Show, Eq)

-- Update the player aim function to calculate the currently looked-at cell

handlePlayerAim :: System World ()

handlePlayerAim = do

windowWidth <- liftIO RL.getScreenWidth

windowHeight <- liftIO RL.getScreenHeight

Camera camera <- get global

ray <- liftIO $ RL.getMouseRay (RL.Vector2

(CFloat $ fromIntegral windowWidth / 2)

(CFloat $ fromIntegral windowHeight / 2)) camera

-- Use the ray we generated to find a target

target <- cfoldM (findLookAtTarget ray) NoTarget

set global $ Aim ray target

-- Look for closest board that the player is looking at

findLookAtTarget :: RL.Ray -> LookAtTarget ->

(BoardComponent, PositionComponent, Entity) ->

System World LookAtTarget

findLookAtTarget ray target (_, Position p, e) = do

-- If our raycast hits the current board

if RL.rayCollision'hit hitInfo > 0 then

-- Check if this new target is closer than our current target

getClosestTarget ray target $ Target e (findCell hitPos)

-- Otherwise, use the current best target

else

pure target

-- Determine where to place the hitbox for raycast, and check hit location

where from = addVectors p $ Vector3 (-1.5) (-1.5) (-0.05)

to = addVectors p $ Vector3 1.5 1.5 0.05

hitInfo = RL.getRayCollisionBox ray $ RL.BoundingBox from to

hitPos = subtractVectors (RL.rayCollision'point hitInfo) p

-- Checks two targets and returns the closest one

getClosestTarget :: RL.Ray -> LookAtTarget -> LookAtTarget ->

System World LookAtTarget

-- If both variables are valid targets

getClosestTarget ray a@(Target eA _) b@(Target eB _) = do

-- Note: We could have passed in the position of the prospective target,

-- but felt a bit rubbish today and just thought I'd keep it simple

Position posA <- get eA

Position posB <- get eB

-- Calculate distances to ray origin

let p = RL.ray'position ray

distA = magnitudeVector $ subtractVectors posA p

distB = magnitudeVector $ subtractVectors posB p

-- Return closest target

pure $ if distA <= distB then a else b

-- Handle cases where invalid targets present

getClosestTarget _ a NoTarget = pure a

getClosestTarget _ NoTarget b = pure b

-- Takes a hit position and determines the looked-at cell

findCell :: Vector3 -> Int

findCell (Vector3 x y _)

| y > 0.5 = findCol 0 1 2

| y < -0.5 = findCol 6 7 8

| otherwise = findCol 3 4 5

where findCol left center right

| x < -0.5 = left

| x > 0.5 = right

| otherwise = center

-- Another utility function to get the length / magnitude of a vector3

magnitudeVector :: Vector3 -> Float

magnitudeVector (Vector3 x y z) =

let CFloat f = sqrt $ (x * x) + (y * y) + (z * z) in fOur PlayerAimComponent is now primed! Let’s render it to prove to ourselves that we’ve completed a major hurdle. As an extra spin, I only want to render these markings if the cell isn’t already filled. We’re going to be pretty much updating all of our rendering logic to accept the LookAtTarget as a new parameter:

renderBoards :: System World ()

renderBoards = do

-- Give the target from our aim component to renderBoard

Aim _ target <- get global

cmapM_ (renderBoard target)

-- Accept a new parameter and forward it to renderCrosses

renderBoard :: LookAtTarget -> (BoardComponent, PositionComponent, Entity) ->

System World ()

renderBoard target (b, Position p, e) = do

renderCrosses p (b, e) target

-- ...

-- Each cross now has an index - we need to check if each cross is being

-- aimed at and pass that to renderCross. We have a new function to handle

-- that: isAimingAtCell

renderCrosses :: Vector3 -> (BoardComponent, Entity) -> LookAtTarget ->

System World ()

renderCrosses origin (b, e) target = do

renderCross origin (-1) 1 (_tl b) (isAimingAtCell e 0 target)

renderCross origin 0 1 (_tc b) (isAimingAtCell e 1 target)

-- ...

-- Checks if the target is valid, and returns true if entity and cell matches

isAimingAtCell :: Entity -> Int -> LookAtTarget -> Bool

isAimingAtCell (Entity e) i (Target (Entity e') i') = e == e' && i == i'

isAimingAtCell _ _ _ = False

-- This function has another pattern to it depending on whether its aimed at

renderCross :: Vector3 -> Float -> Float -> Cell -> Bool -> System World ()

-- Empty, non-aimed at cells have nothing rendered

renderCross _ _ _ Empty False = pure ()

-- Filled cells are rendered as crosses, regardless of aim

renderCross origin i j Filled _ = liftIO $ do

RL.drawLine3D (f (-0.4) (-0.4)) (f 0.4 0.4) RL.red

RL.drawLine3D (f 0.4 (-0.4)) (f (-0.4) 0.4) RL.red

where center = addVectors origin $ Vector3 (CFloat i) (CFloat j) 0

f x y = addVectors center $ Vector3 x y 0

-- Otherwise, if we have an empty cell that's aimed at, render a circle

renderCross origin i j Empty True = liftIO $ do

RL.drawCircle3D center 0.4 (Vector3 0 1 0) 0 RL.yellow

where center = addVectors origin $ Vector3 (CFloat i) (CFloat j) 0And with this, it’s game over! From now on it’s mostly gameplay code, and hopefully everything we do can is reflected by our rendering! Well done if you’ve made it this far; like with most games, the rendering can easily eat up a lot of our time. I’m sure the only rendering we’ll do from now on will be trivial.

We can now aim at cells, rendering the game is pretty much complete!

A link to the corresponding commit for the previous section can be found here.

Placing crosses dynamically

I don’t know about you, but I really hate the fact that this blog post so far has been mostly rendering! Isn’t this meant to be a blog about Apecs?! Well, let’s fix that by finishing our game and coming up with more entities, components and systems! First up are a set of systems to handle playing the game.

So far, our game has been doing all of our systems every single frame — we need to have some logic ran conditionally:

- Obviously, we need to place crosses when we click: We wouldn’t want this running every frame as the game would be unplayable!

- When we get three-in-a-row we need to kill the board: The state of the game only changes when moves are made, so this can also be ran on left click; it would be redundant otherwise!

- We need to check for game-over when a board is killed: When there are no boards remaining, the current player is the loser and the winner is decided. Again, this relies on state being changed, so we’re slowly moving away from frames to turns.

- We need to switch players: We have no concept of players yet, but when we do, we will be switching who’s turn it is as well as incrementing stats of whatever sort after checking for game-over and it being decided that play should be continued.

update :: System World ()

update = do

updateCamera

handlePlayerAim

-- After aiming, we want to handle clicking

clicked <- liftIO $ RL.isMouseButtonPressed 0

when clicked $ do

handleLeftClick

-- Handles everything that may happen following a left-click

handleLeftClick :: System World ()

handleLeftClick = do

-- Try and place a cross, and print a message when successful

moveMade <- tryPlaceCross

when moveMade $ do

-- Note: This is where we'll check for game-over later

liftIO $ putStrLn "Move Made!"

-- This system returns true if a new cross is placed on the board

tryPlaceCross :: System World Bool

tryPlaceCross = do

-- Get the player's target

Aim _ target <- get global

case target of

-- Do nothing if there is no target

NoTarget -> pure False

-- If there is a target, try to mutate the state of the board

Target e i -> do

board <- get e

if getCell board i == Empty then do

-- We set the component on the entity here directly,

-- if you're doing this on lots of entities you should be using cmap

set e $ setCell board i Filled

pure True

else

pure False

-- Convenience function for retrieving a cell by-index

getCell :: BoardComponent -> Int -> Cell

getCell b 0 =_tl b

getCell b 1 =_tc b

getCell b 2 =_tr b

-- ...

-- Convenience function for setting a cell by-index

setCell :: BoardComponent -> Int -> Cell -> BoardComponent

setCell b 0 c = b { _tl = c }

setCell b 1 c = b { _tc = c }

setCell b 2 c = b { _tr = c }

-- ...If you give the game a try now, you’ll be happy to see that, as expected, we can now place crosses when we click the mouse button. We have a lot of momentum now, let’s not stop here and move onto finishing the game loop itself!

A link to the corresponding commit for the previous section can be found here.

Killing boards

The rules of Notakto state that when a three-in-a-row is detected, a board is declared ‘dead’ and can no longer be played on; when there are no boards remaining, the game is over and the current player loses. Killing boards is just as important as making moves on a single board, however fortunately for us this won’t be difficult at all to pull off with the tools we have.

- We will create a new component that we attach to boards to render them dead: We could calculate if a board is dead every time we need to know, but this will add up especially if we want to render this somehow. If we use a component, we can trivially iterate through alive and dead boards.

- We will count the dead boards: We will use

cfoldto count the number of boards that are alive, and if this number is 0 we will declare the game to be over. - We will not render dead boards: I’m stick of doing rendering in this tutorial. I’m going to force the players to manually check the state of the board for whether they’re playable — it’s not a missing feature, it’s a skill check.

-- New component with a unary data constructor

-- Note: To test for absense, we will be using the type Not DeathComponent

data DeathComponent = Dead deriving (Show, Eq)

-- New system that will kill any boards with three-in-a-row and

-- then return if there's a game-over

checkForGameOver :: System World Bool

checkForGameOver = do

-- Map a function onto all entities with boards, killing them if possible

cmap tryKillBoard

-- Count the number of boards that are alive (lack of death component)

let countAlive :: Int -> (BoardComponent, Not DeathComponent) -> Int

countAlive c (_, _) = c + 1

-- Perform the counting and return true if all boards dead

count <- cfold countAlive 0

pure $ count <= 0

-- Note the type signature; we use 'Not' to exclude dead boards

-- Another thing to note is that we return 'Maybe DeathComponent',

-- this hints that we may or may not be adding a component to the entity

tryKillBoard :: (BoardComponent, Not DeathComponent) -> Maybe DeathComponent

-- Just Dead will add the DeathComponent, Nothing will add nothing

tryKillBoard (bc, _) = if check cellCombos then Just Dead else Nothing

-- Fold through a list of combos and check if any are threes-in-a-row

where check = foldl (\dead (a, b, c) -> dead || checkCombo a b c) False

-- Check if all cells in a combination are filled, meaning a win

checkCombo a b c = checkCell a && checkCell b && checkCell c

checkCell c = getCell bc c == Filled

-- A list of all cell combinations in index form (to be used with getCell)

cellCombos :: [(Int, Int, Int)]

cellCombos = [

-- Horizontal

(0, 1, 2),

(3, 4, 5),

(6, 7, 8),

-- Vertical

(0, 3, 6),

(1, 4, 7),

(2, 5, 8),

-- Diagonal

(0, 4, 8),

(2, 4, 6)

]You may think that’s it, but now we need to sprinkle mention of the DeathComponent to places where we don’t want interactions with dead boards. After looking through the code, I can only think of one place, but you might have more:

findLookAtTarget :: RL.Ray -> LookAtTarget -> (BoardComponent,

PositionComponent, Not DeathComponent, Entity) ->

System World LookAtTargetIf you want to special rendering for dead boards, now is the time! You might even want to update the death component to contain data regarding the winning combination for easy access!

Let’s now use our new system in the game and print a message if the game is over:

handleLeftClick :: System World ()

handleLeftClick = do

moveMade <- tryPlaceCross

when moveMade $ do

isGameOver <- checkForGameOver

if isGameOver then

liftIO $ putStrLn "Game over!"

else

liftIO $ putStrLn "Next turn!"

We can now detect a game over — it’s all coming together!

Restarting the game

Before we finish this chapter, let’s handle restarting the game as it’s very related to the previous section! Firstly, even though we named the function checkForGameOver, this function is also responsible for killing boards. Let’s do this elsewhere so that this function is purely a check, this way we can reuse it without worry!

handleLeftClick :: System World ()

handleLeftClick = do

-- Check if the game is already over before making a move

needsRestart <- checkForGameOver

-- Only make moves if the game isn't over

if not needsRestart then do

moveMade <- tryPlaceCross

when moveMade $ do

cmap tryKillBoard

isGameOver <- checkForGameOver

if isGameOver then

liftIO $ putStrLn "Game over!"

else

liftIO $ putStrLn "Next turn!"

-- Otherwise, restart the game

else do

newGame

liftIO $ putStrLn "Restarted game!"

-- New initialisation function that deletes all entities

newGame :: System World ()

newGame = do

cmapM_ deleteBoard

createBoards 3

-- You can't really 'delete' entities in Apecs since entities are just ints;

-- you have to delete their components. We use a convenience function.

where deleteBoard (Board{}, e) = destroyEntity e

-- We make a type combining all types for miscellaneous use

type AllComponents = (PositionComponent, CameraComponent, BoardComponent,

DeathComponent, PlayerAimComponent)

-- Trivial deletion function

destroyEntity :: Entity -> System World ()

destroyEntity e = destroy e (Proxy :: Proxy AllComponents)Deletion in Apecs can be a little tricky, but as the author writes in this comment, as long as we obliterate any components on an entity it will stop having any effect on the application!

You can’t destroy an entity, you can only destroy each of its components. An Entity is just an integer that may or may not some components associated with it. There is currently no way to destroy all components for a given entity.

I might add some support for this in the future, but if you use type synonyms for common tuples, it shouldn’t be an issue.

Apecs author Jonascarpay talking about deletion in Apecs.

Well done, you can now play, complete and restart games! If you were to track turns and play with a friend, you could call this the end and enjoy it! There’s one final thing I want to do before I call quits and leave the rest up to you: creating the notion of players!

A link to the corresponding commit for the previous section can be found here.

Making players take turns

The game is essentially complete, but we don’t really track the current player anywhere! I’m going to leave out the rendering and purely focus on the components and systems as I’m sure anyone reading this can fill in the gaps.

-- New component for tracking the current player

data PlayerComponent = Red | Blue deriving (Show, Eq)

-- Initialise the current player when we initialise the camera

set global $ (Camera camera, Red)

-- Switch players when a non-winning move is made

handleLeftClick :: System World ()

handleLeftClick = do

-- Grab current player

player <- get global

needsRestart <- checkForGameOver

if not needsRestart then do

moveMade <- tryPlaceCross

when moveMade $ do

cmap tryKillBoard

isGameOver <- checkForGameOver

if isGameOver then

-- Print that the current player lost

liftIO $ putStrLn $ "Game over! " ++ show player ++ " loses!"

else do

-- Swap players and print who's turn it is

let nextPlayer = if player == Red then Blue else Red

set global nextPlayer

liftIO $ putStrLn $ "It's " ++ show nextPlayer ++ "'s turn!"

else do

newGame

liftIO $ putStrLn $ "Restarted game! It's " ++ show player ++ "'s turn!"

-- Change colour of things for different players

playerColour :: PlayerComponent -> RL.Color

playerColour Red = RL.red

playerColour Blue = RL.skyBlue

-- Example of changing colour of ray to suit player

renderAimRay :: System World ()

renderAimRay = do

-- Notice that we aren't annotating the type for player; we infer it!

(Aim ray _, player) <- get global

let lineStart = addVectors (RL.ray'position ray) (Vector3 0 (-0.05) 0)

lineEnd = addVectors (RL.ray'position ray) $

multiplyVector (RL.ray'direction ray) 10

liftIO $ RL.drawLine3D lineStart lineEnd $ playerColour playerFirstly, how cool is it that we can add features to the game this easily when using both Haskell and Apecs? It’s really during the iterations on your project where Haskell shines, and Apecs complements it perfectly. Secondly, notice that we didn’t annotate the type for player — again, thanks to Haskell, we can infer the types of components from their usage, so as long as you use your components for things you typically don’t have to be explicit with what the result of get needs to be. We’ve been mostly explicit up until now as we wanted to pattern match, but the PlayerComponent is very simple.

Here is where I set my first challenge — this blog post is becoming way too long, and so I’m going to make a change and show you how cool the result is, and you’ll have to make the changes yourself! Of course, the repository can be found at the end of the section with a link to the commit, so if you get stuck you can look up how I managed it. These changes are small and numerous; too boring to put write up. Have fun and see you in the next section!

-- We are going to annotate each cell with the player who placed the cross

data Cell = Empty | Filled PlayerComponent deriving (Show, Eq)

-- CHALLENGE:

-- 1. Change colour of crosses to be dependent on player

-- 2. Change circular 'aim' indicator to match player colour

-- 3. Have fun!

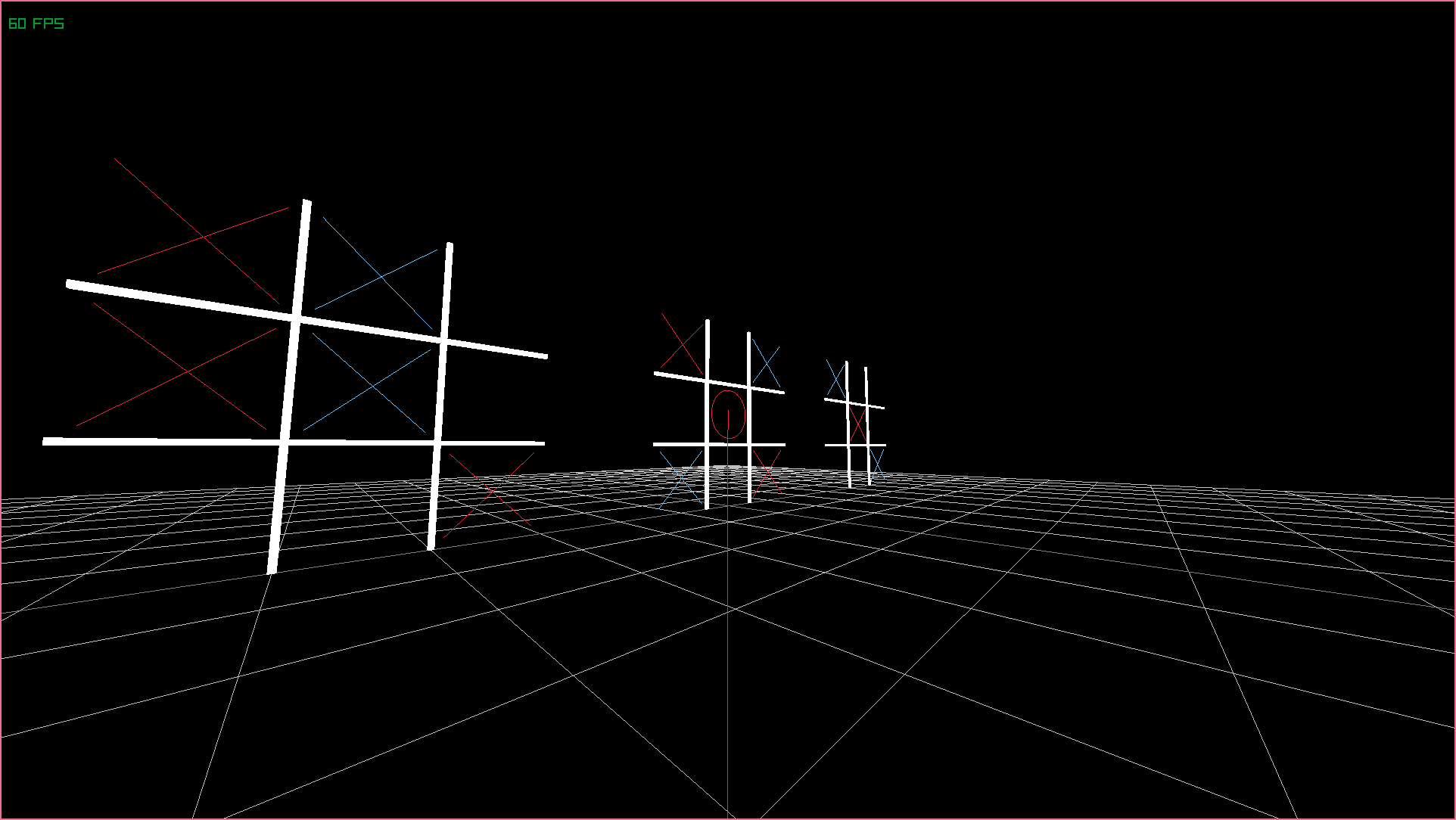

It’s heating up; it’s red vs blue!

A link to the final section can be found here.

Bonus: Manually implementing first-person camera

Okay, so I’ve spied online that this post is actually being read and people are posting it around on Reddit (thankyou!). With that in mind, I thought I’d update the repository so that newer Haskellers can use the code without as many issues. One of the biggest things I found is that the camera was no longer moving on its own.

This was actually something that worried me when using Raylib at first, as it felt too ‘magical’ that their demo just baked in the first person camera movement. Fortunately, this isn’t hard to do, and so here’s the code:

-- Had to update this system to return the window we create

-- Also note that we disable the cursor straight away for free look

initialise :: System World RL.WindowResources

initialise = do

let camera = RL.Camera3D (Vector3 0 1 6) (Vector3 0 1 0) (Vector3 0 1 0) 90

RL.CameraPerspective

set global (Camera camera, Red)

newGame

liftIO $ do

window <- RL.initWindow 1920 1080 "App"

RL.setTargetFPS 60

RL.disableCursor

pure window

-- Also changed terminate to close the specific window we created

terminate :: RL.WindowResources -> System World ()

terminate window = liftIO $ RL.closeWindow window

-- We now manually manipulate the camera's location and rotation

updateCamera :: System World ()

updateCamera = do

Camera c <- get global

newCam <- liftIO $ do

dt <- RL.getFrameTime

forward <- checkKey RL.KeyW RL.KeyUp

left <- checkKey RL.KeyA RL.KeyLeft

backward <- checkKey RL.KeyS RL.KeyDown

right <- checkKey RL.KeyD RL.KeyRight

Vector2 i j <- RL.getMouseDelta

let speed = 5.0

turnspeed = 1

Vector3 x _ z =

(RL.getCameraForward c |* (forward - backward)) |+|

(RL.getCameraRight c |* (right - left))

c' = RL.cameraMove c $ safeNormalize (Vector3 x 0 z) |* (speed * dt)

c'' = RL.cameraYaw c' (-i * turnspeed * dt) False

pure $ RL.cameraPitch c'' (-j * turnspeed * dt) False False False

set global $ Camera newCam

where checkKey a b =

liftA2 (\x y -> if x || y then 1 else 0) (RL.isKeyDown a) (RL.isKeyDown b)

safeNormalize v

| magnitude v == 0 = v

| otherwise = vectorNormalize vSome things to note here is that a lot of our vector math functions are built into the h-raylib bindings now, so |+| lets you add two vectors together, |*| lets you multiply two vectors together, |* lets you multiply a vector with a normal scalar value and so on.

So with that in mind, we now retrieve the state of several keyboard inputs one by one and determine which direction we want to move in by combining the player’s net input as well as the camera’s forward and right directions. We then normalize that (I had to make a safeNormalize function for cases when magnituded is zero, this will probably get fixed soon) and multiply it by some speed value and delta time to make it frame independent. Looking around is similar; Raylib already gives us the mouse delta so we can put the right into the look direction logic.

Make sure to check out the diff for all the changes I made in this update. I hope this helps!

Wrapping up

Congratulations! I’m hoping that the content of this post, although long, has been useful as a gateway into the world of Haskell game development. I really enjoyed making this post and I’m hoping my readers enjoyed this new format even if it is a little wordy.

There are no more sections for this blog post, although honestly I wanted to go wild and do things like:

Projectiles: When you click, you shoot a cube and you have to land it in a cell for it to mark. Would be interesting to make it so that you can only shoot if no projectile currently exists, and making the actions that happen when you click the mouse delayed until the projectile lands. Good luck finding that shot when it goes out of bounds!

Moving boards: We have a

PositionComponentbut the data never really changes once created. Wouldn’t it be fun to make the boards fly around?Rotated boards: Right now we assume all boards face the same way. Adding a rotation would be fun but a little bit of work since you may need to write your own vector math functions unless you use another library (I wanted the dependency count to be low for this post).

Forced distance: I wanted to make it so that you could only take a turn if you were stood in an area, so that you had to aim. Would be cool making a little environment with player colouring!

AI: Here’s an easy peasy one — make it so that when you make your move, you can get an AI to play as the other person! Start off by just randomising the entity and cell index, and once you you’ve got a very basic AI you can move up to implementing the Negamax algorithm!

These things all sound fun, but I believe that the important thing is to teach the basics of Apecs and Raylib so that we get more projects popping up in the Haskell gamedev space. I’ve seen a lot of cool projects like Keid, but admittedly I just love Apecs too much, and now I can love Raylib also (even if I haven’t explored its limits too much).

Big thankyous to:

- Jonas Carpay, author of Apecs,

- Anand Swaroop (Anut-py) for creating the h-raylib bindings,

- the authors of Raylib,

- and finally, the Nix community for helping me with all my problems whenever I go crying to them about something not working. Really, thanks guys!

If anyone wants anything from this blog revised, has feedback, or just wants to talk, you can get in touch via contact@aas.sh. Looking forward to hearing from you!

And with that, I’m signing off. Thank you for reading!