I’ve always been aware of the Lisp language family, but always been afraid to dive in. It was always mysterious and taking the forms of various languages. However, after being shown the book ‘Clojure for the brave and true’ by Daniel Higginbotham, I now recognise Clojure as a simple, pleasant and powerful language that everyone should try. Clojure is a dynamically typed language, meaning that while it is functional like Haskell (my favourite language), it is an entirely different experience to write. Rather than starting your implementation thinking about types and converting the flow of data from type to type, you instead start thinking about everything the Lisp way.

The basics

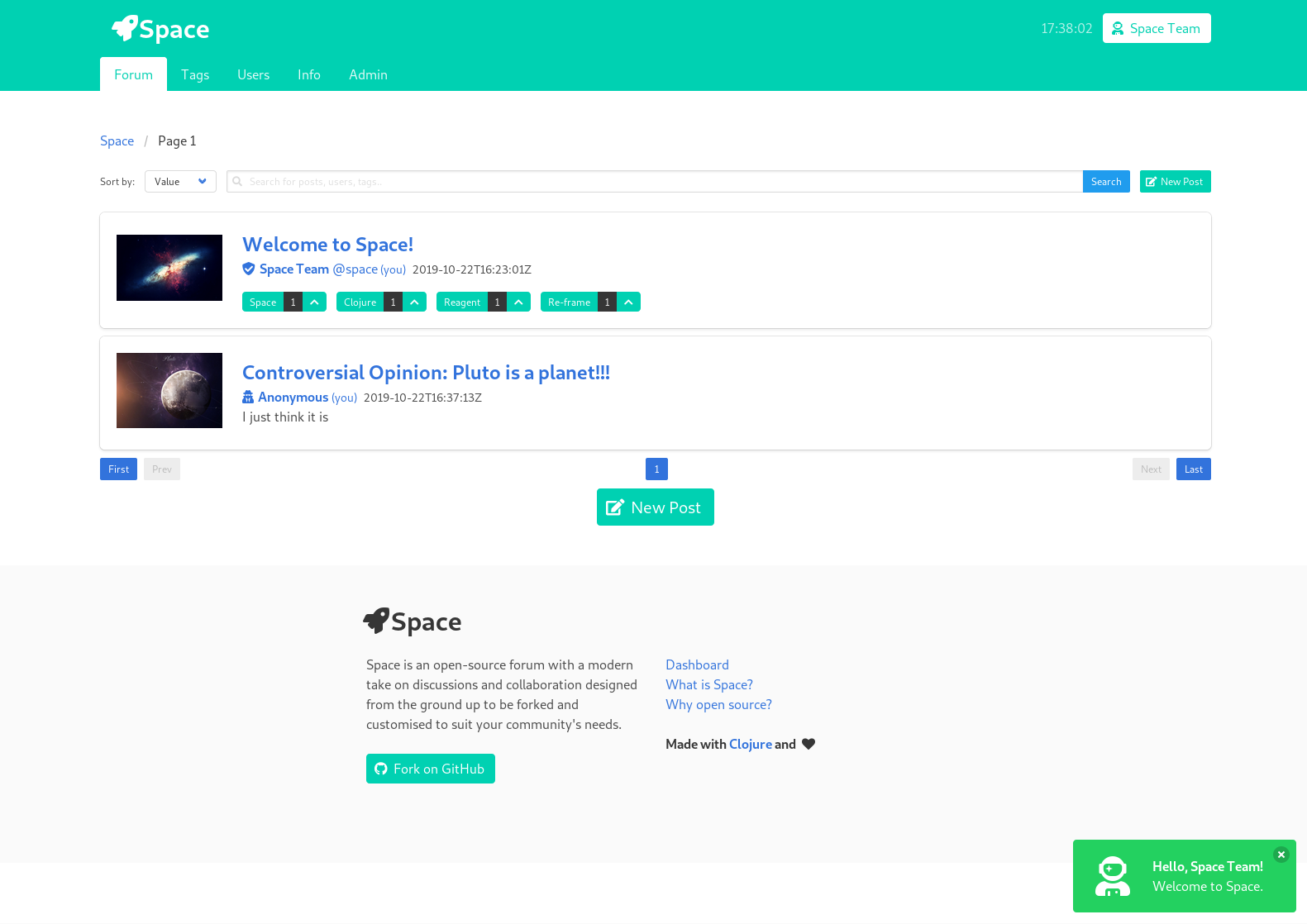

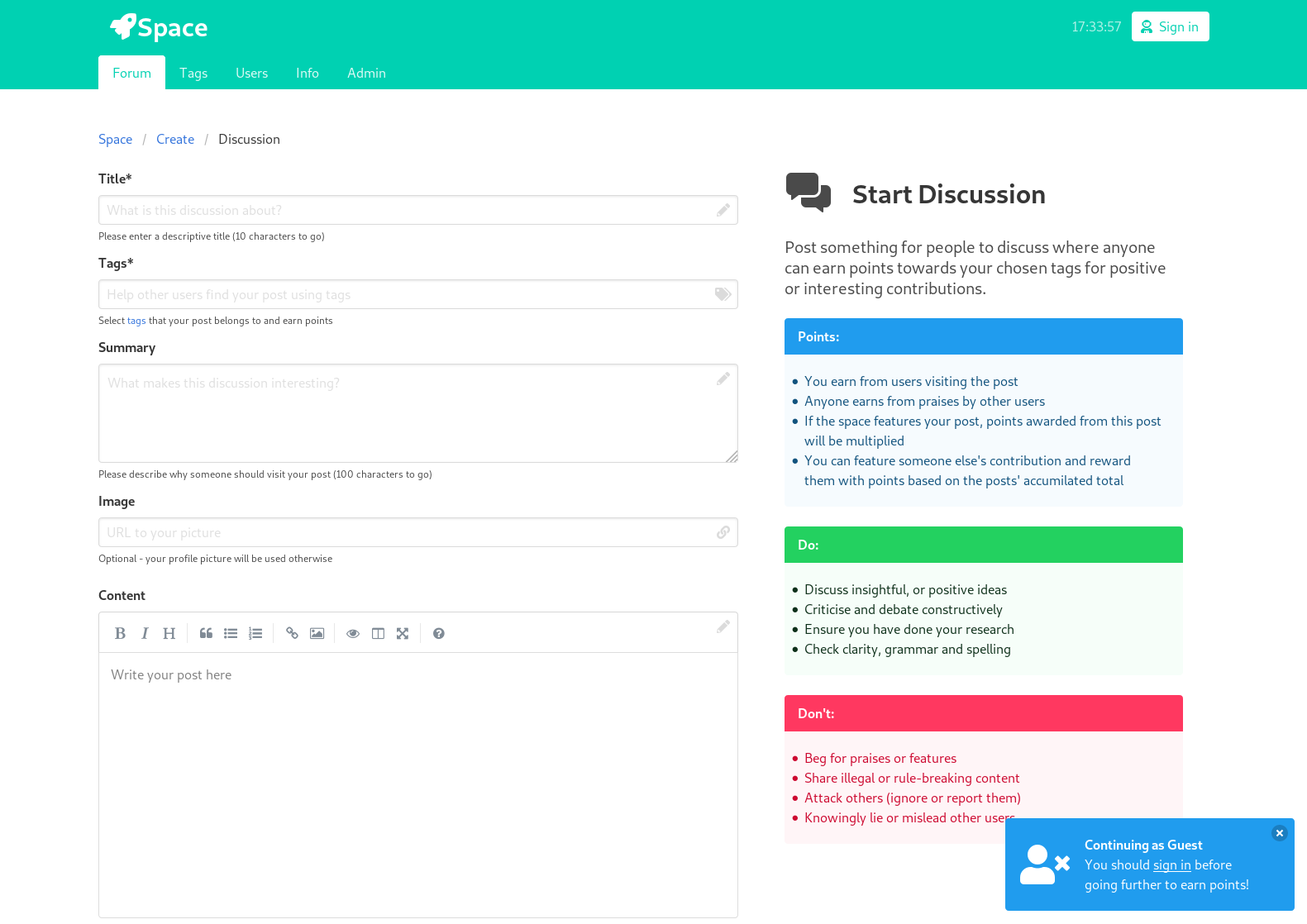

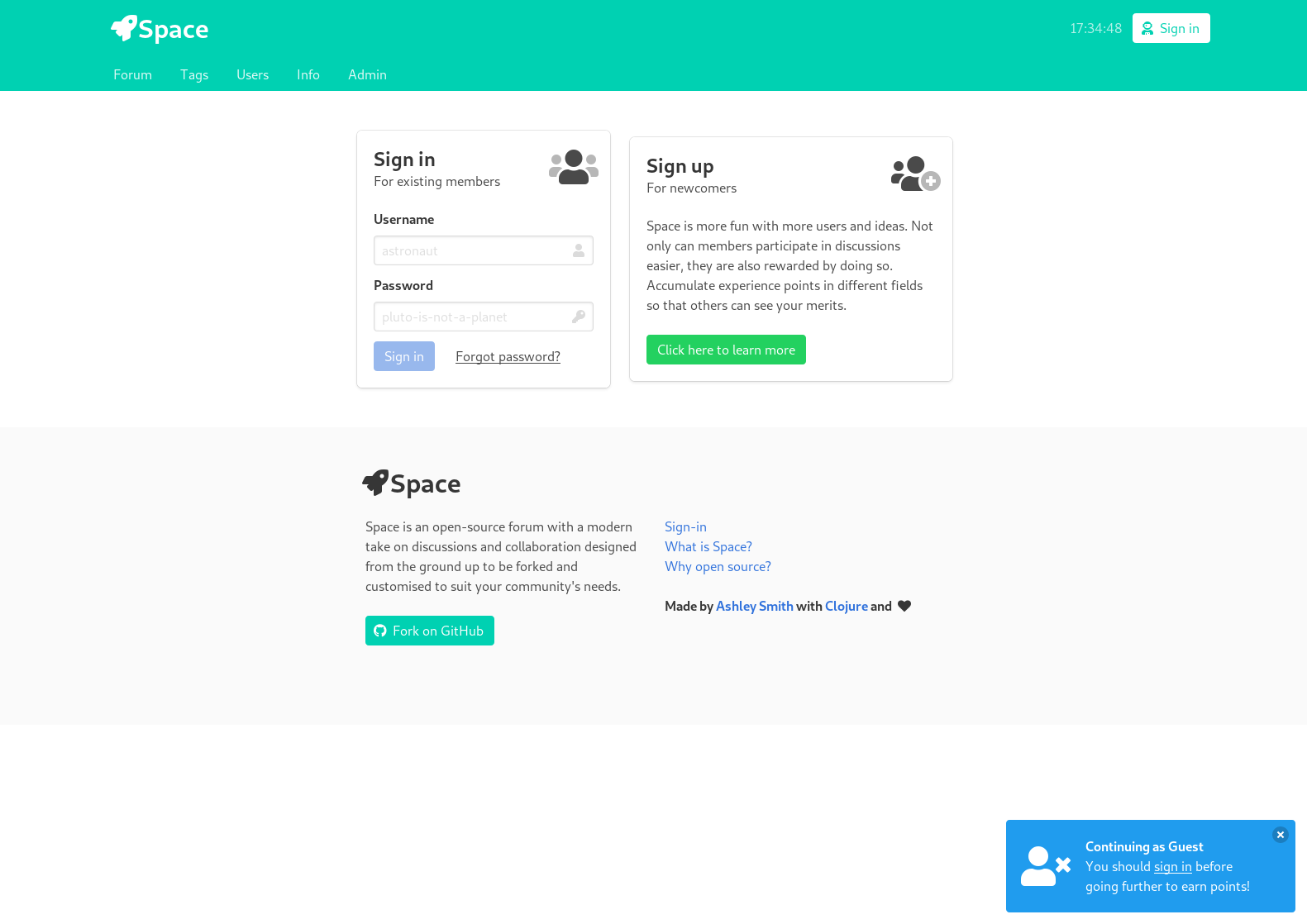

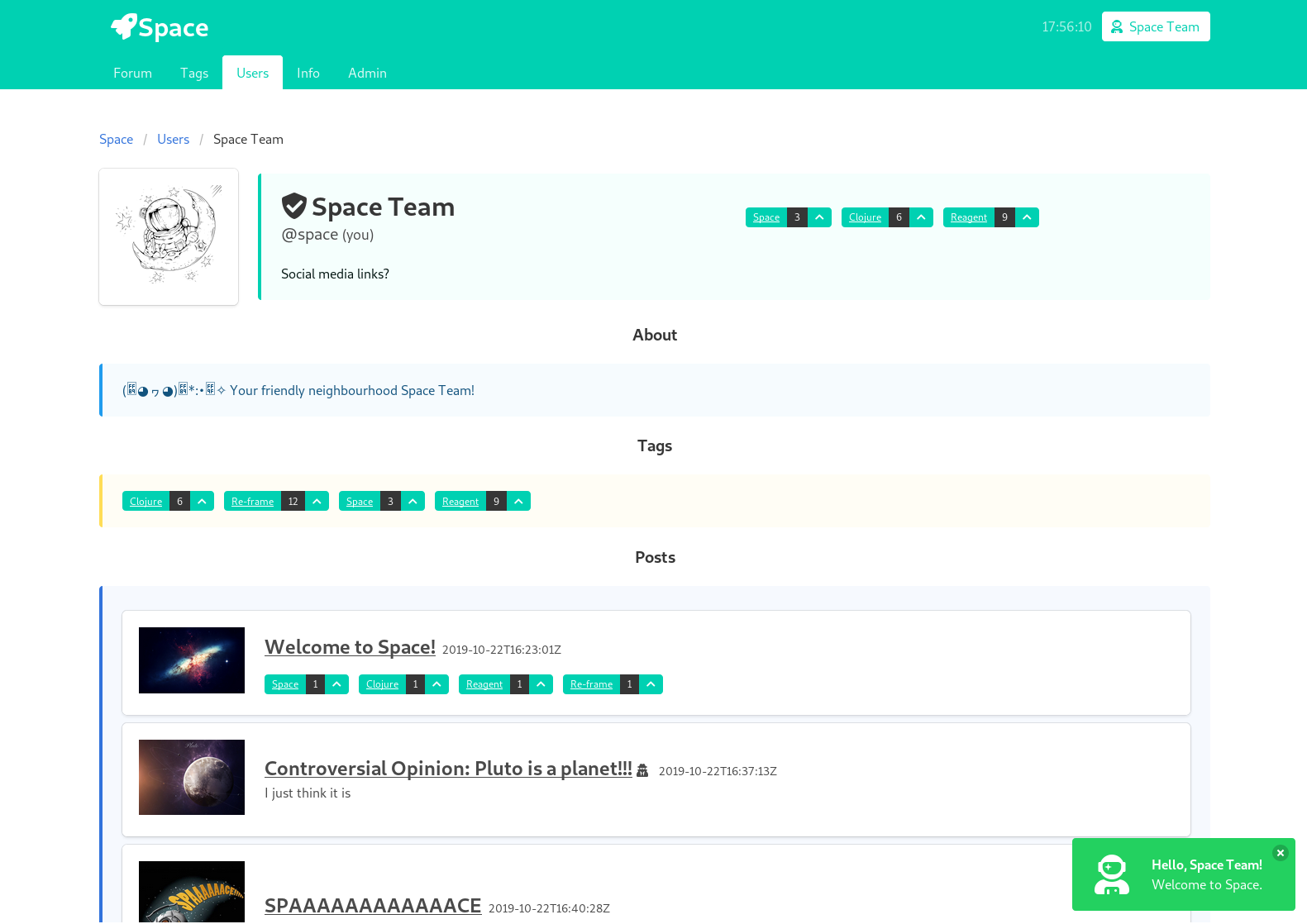

I didn’t really recognise what this meant until I had learned enough Clojure to begin using libraries made by other people. I had begun Space and was thoroughly enjoying taking a deep dive into using Clojure with a package called Reagent, a way of using Facebook’s React. In order for me to show how cool Clojure is though, I need to give a quick run down on what a function looks like. With the help of Brave Clojure, I can tell you now that anyone can learn this in about 2-3 weeks. The language itself is simple, and while the concepts may get a little complex, it is nowhere near as complex as Haskell to get simple programs going.

Clojure runs on the JVM and can interact with Java in a similar way to how C++ can interact with C (although the way they’re written is no where near as similar as C++ and C are). Also like Java, ClojureScript exists and writes in pretty much the same way as regular Clojure, and ClojureScript can interact with JavaScript just like how Clojure can interact with Java — yes, this means that you may not need to write any JS code for your web app!

I don’t want re-write Brave Clojure (yes I will plug this book every time I reference it as it is absolutely incredible) as frankly there’s nothing to improve on. I’ll only explain what I feel is necessary for this blog post.

; Global, immutable variable

(def the-number-one 1)

; Print it

(print the-number-one)

; Function call example (returns 6)

(+ the-number-one 2 3)

; Function definition

; Note: The last line is what is returned

(defn add-one-to-number

"This is a docstring, it should describe the function."

[num]

(+ num the-number-one))

; Declare a vector

(def a-vector [1 2 3])

; Add one to everything in the vector and print it

; Note the braces ARE NOT optional unlike Haskell where sometimes they can be

(print (map add-one-to-number a-vector))Every function call in Lisp uses braces and no commas. You put the function name at the start, and then all it’s parameters afterwards. If you know Haskell, note that currying isn’t done by default (use the function partial if you want to partially apply functions). While there are plenty more features, I’m not going to go into everything as, again, Brave Clojure covers everything you need to know. However, there are a few things I do need to draw attention to regarding the parameter for add-one-to-number.

First, Clojure is dynamically typed, and so while it might be obvious we’re talking about numbers, as long as the + function accepts the right type, this function will work. We don’t need to specify a variable or group of variables like in Haskell, as it is dynamic.

Second, the entire line is the parameter. If you’re familiar with Haskell’s pattern matching for binding variables, this is similar. [num] represents a vector with num being the first element. With Clojure being a dynamic language, anything can be nil, so this doesn’t break if the vector is empty as long as num is checked to not be nil. Here’s some more examples to illustrate this functionality:

; Add one to a number and print the result before returning

; Note: docstrings are optional

; Note: new-num is NOT a function but a variable and so there's no braces

(defn add-one-to-number

[num]

(let [new-num (+ 1 num)]

(print new-num)

new-num))

; Add two numbers

(defn add-two-numbers

[a b]

(+ a b))

; Print all elements given as a vector

; Note: This will place elements into a vector for printing purposes

(defn print-args

args

(print args))

; Function with optional arguments

; Note: Optional arguments come after the & in their own vector

; Note: This isn't a good idea as other arguments given are silently ignored

(defn print-up-to-two-nums

[& [a b]]

(print a)

(print b))

(print-up-to-two-nums 1 2 3) ; => prints 1 and 2, 3 is ignored but consumedIt should be noted that with the use of let to bind a value, the variable new-num is only accessible within the scope of the let call. It cannot be used outside the braces surrounding the let call. It may look unreadable to some people but you soon get used to the number of braces used while writing Lisp code.

A dumb but funny lisp meme.

Now lets look at that Reagent library again.

(defn some-component []

[:div

[:h3 "I am a component!"]

[:p.someclass

"I have " [:strong "bold"]

[:span {:style {:color "red"}} " and red"]

" text."]])Don’t be frightened! Let’s break it down. Firstly, the parameter list is on the same line as the function name, and so [] indicates this function takes no parameters. We know it’s a function, as defn is used as opposed to def, indicating that it’s a function and not a variable. Things starting with a colon, such as :div, :h3 or :p.someclass are keywords — they are sort of special, but they can be treated similar to strings in the sense that you can print them, check for equality etc. This is where things get interesting, as it’s the first time I was exposed to the Lisp philosophy:

Code-as-data, Data-as-code: the idea that you can use data structures to represent executable code.

Code as Data: Thinking differently

If you’ve done any amount of web development, that snippet may have some meaning to you. If you look carefully at the structure, you can see that the Vectors are both nested and containing various different types. Try flattening the vector in your head and you’ll see that it is just one long list of variables, starting with :div, then another Vector containing :h3 and "I am a component!", and so forth.

Looking at Reagent’s readme, you can see that Hiccup is used to represent HTML. Hiccup will take one long Vector of data and turn it into something Reagent can use. As mentioned, Reagent allows you to use React with Clojure, which allows you to create web apps. To put it in layman’s terms, that snippet allows you to create a website without writing standard HTML! Let’s go into more detail:

; Vector of stuff. Imagine if you got this from some database or user interaction

(def names ["Ashley" "Totoro" "Kiki"])

; Bullet point list of names

; This function maps an anonymous function onto the above Vector

; This anonymous nothing but returns another Vector with :li prepending the name

(defn some-component []

[:div

(when (not (empty? names))

[:h1 "Cool people:"])

[:ul

(map

(fn [name]

[:li name]))

names]])

; This is how you'd combine components together

(defn your-web-page []

[:div

[header]

[navbar]

[:article

[content]

[some-component]

[some-other-component]]])I tried to be a little more complex with this example. We have some data in names of some pretty cool characters. The goal is to create a way of dynamically rendering each of these names to the page (in Reagent, the page will actually change if you use a mutable variables using atoms) without hard coding or doing anything laborious. The function When takes two parameters, the first being a condition and the second being absolutely anything you want this function call to evaluate to when true as opposed to being nil when false. The page will only say Cool People: if there’s one or more elements inside names. Hiccup will ignore any nils inside data, and so if names does become empty, the element simply disappears from the DOM.

Next, a function is mapped onto every name in names. This function transforms the element into another Vector with :li (for list-item). If there are no elements in the vector, nothing will appear similar to the "Cool People" message. This results in a web page that is responsive to changes in data, just like any other React app — but with the advantages of a language like Clojure.

Finally, when calling using the functions, we wrap them into Vectors as we aren’t actually calling them here — while we could call them, Hiccup will handle it for us if we use Vectors. While there’s some technical differences between the ways you use your own components, it’s pretty easy either way. Passing functions around inside Vectors without calling them is quite common too, depending on the frameworks you use.

This rabbit hole goes as deep as you like, and this philosophy of swapping data with functions interchangeably is a powerful one. I used Clojure for the API server of Space as well as the front-end, and the idea of code and data being the same thing is very consistent with all of the libraries I used. While Haskell’s libraries like to define their own monads and types, Clojure’s libraries all seemed to deal with plain types and Keywords and so they could use each other’s data easily. Remember that a Keyword is like a String, so there’s no special construction mechanism or any rules for passing them around, they can be used in the same places that Strings are and are typically used for special interactions with the libraries you find, as you can see in the above snippets.

Final thoughts

Clojure is great, and I learned the basics in a week and a half all thanks to Brave Clojure. The braces can get a little overwhelming at first, but once you overcome it, Lisp code is very pleasant to work with. It is a dynamic language, so it does sacrifice safety for ease — I think writing web-apps is a perfectly valid use case for Clojure but I’d still consider using Haskell’s type system so that the compiler can help me avoid faults before they occur. In Clojure, special variables are hard to come by with everything being plain data, and so the only times you’ll really get faults are when you try using a variable as a function, or if you use a function as a variable and the thing receiving it can’t handle it. Without static typing, it’s easier to get things done but harder to prevent runtime errors without caution.

Haskell is entirely pure, and printing things to the screen can get a little tough especially when you’re trying to inject print messages into other functions (you’ll infect everything with the IO Monad etc, I won’t go into it but you can get around it). In Clojure, Monads aren’t really a thing, and the language itself isn’t strictly pure although pure functions are highly encouraged and incentivised. This means that you can do multiple things with the same function, like when I printed a number and then returned it in one of the snippets above. Again, Clojure is easy and lovely to work with. I still love Haskell and it’s type system, I can certainly see many valid situations where I’d definitely use Clojure over Haskell.

Thanks for reading.