Before I touched Haskell, I felt pretty savvy about using CMake for my C++ projects. My mind started expanding as I started to learn both functional programming and the tools that work declartively. I hope that this post is a good introduction to the world of Nix for beginners.

The build tool evolution

Typically when working with Haskell, you’d use something like Stack or Cabal to declare dependencies and build the project. This works great most of the time, but sometimes they feel like the thorn that makes me reconsider using Haskell.

I started off with Stack since that’s what most tutorials have you install when you’re a beginner (with good reason too, as it is very nice). However, before Stack there was Cabal which is a lot simpler than Stack and focused on resolving dependencies. Stack introduces things like better project templates, caching of built packages and finally usage of Stackage to pull dependencies.

When we mention ‘cabal’ there are actually two things we could be referring to: the library or the build tool cabal-install. The library is used by Stack to help resolve dependencies, meanwhile cabal-install is replaced by Stack. cabal-install pulls dependencies straight from Hackage whereas Stack pulls from Stackage. Stackage one-ups Hackage in usage because the packages are curated to make sure dependencies work with each other (Stable Hackage).

Enter Nix

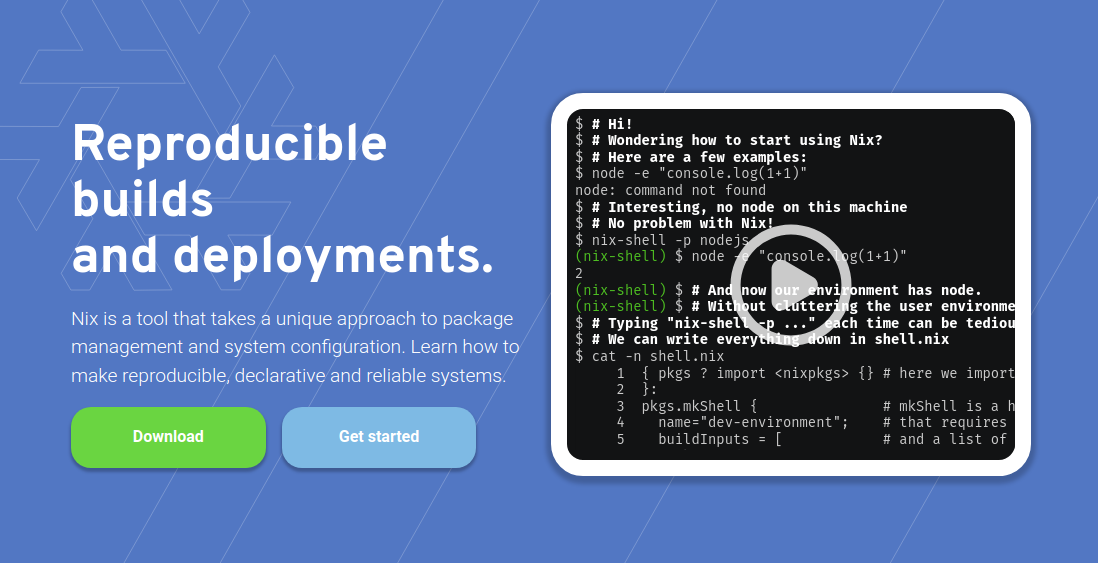

There exists yet another build tool: Nix. The easiest way to describe it is that Nix is like Stack except not just for Haskell. Stack is built very intelligently, keeping different versions of dependencies separate from one another while also keeping track of what’s compatible.

Take C++ development for example — typically, you have to download dependencies and manage them yourself. You might put them in a centralised place on your machine so that all of your programs can find them, but then you force other people to have to put them in the same place. You might consider bundling them with your project as a git submodule, but then you’re requiring users to download all your dependencies even if they already have them on their machines (possibly incurring additional compilation times too). Maybe you have a tool that intelligently searches for the locations of these dependencies, but then you’re requiring users to depend on that tool as well. Even if you’re a solo developer, you are a user of your own work.

In this regard, Stack (along with other build tools like Cargo for Rust is a brilliant improvement on this workflow. However, then you need to install each of these build tools for each of the languages your to-be-built programs and libraries use.

This is where Nix comes in. While sometimes these tools cannot be avoided, they can at least be automated. When using Nix, all of these programs can be built, used and depended-on in the exact same way, while keeping the benefits of reproducability (or bringing, if the old build tools didn’t do these things first).

Nix is a reproducable, declarative and reliable way of building and deploying software.

- Reproducible: Nix builds packages in isolation from each other. This ensures that they are reproducible and don’t have undeclared dependencies, so if a package works on one machine, it will also work on another.

- Declarative: Nix makes it trivial to share development and build environments for your projects, regardless of what programming languages and tools you’re using.

- Reliable: Nix ensures that installing or upgrading one package cannot break other packages. It allows you to roll back to previous versions, and ensures that no package is in an inconsistent state during an upgrade.

Information taken from the official Nix website found here.

When you use Nix, you don’t need to manually install anything related to your project. I have no traces of Rust or C++ on my machine since the only time I need them is during a project where I can let Nix do the heavy lifting. It really is wonderful when you type nix develop and all of a sudden your shell becomes capable of building, testing and running your work. It’s beautiful.

I’ll probably write some tutorials about Nix at some point, but I’m still learning it myself and have yet to actually submit a package to the ecosystem. I just wanted to participate in some evangelism and mention it on my website.

Why do I use Nix?

Regular readers of this blog (read: nobody) will have noticed that I’ve sneakily edited-in this last section. The reason for this addition is simple: I am not well versed enough in nix to really give an overview of its inner-workings and technicalities. What I can do is give a simple overview of my own experience and usecases.

In the past, my website has caused me hassle as every time I wanted to edit it I’d have to set up haskell on whatever machine I was on, which at the time could have been many. It wasn’t too difficult, but was annoying enough to put me off from working on it. This feeling permeated throughout all my projects; any subtle things I did during setup of one machine lead to me needing to repeat them on the others, increasing the probability of human errors and/or unforeseen circumstances which may result in things going wrong.

Nix fixes these things for me. Admittedly, there is a big up front cost whenever I start a project and more often than not you’ll see me frequent the nix discord server asking for tips for architecting and requesting for packages. There is a big reward associated with this though — once I’ve sucessfully set up a project, it is 100% reproducible so long as my machine has the nix package manager. Previewing my website locally is as easy as nix run ., and all my other projects are just as easy to execute.

Recently I was given the opportunity to work with the windows subsystem for linux which meant that I could open up a terminal that was running a linux distribution from within Windows. Fortunately, my dotfiles were separated into system and user configurations, meaning that I could reproduce my text editor and shell experiences on Windows! A huge win!

Each time I set up a new project, I gain a bit of experience as well as a template for me to reuse in future projects. Just like CMake, I’ll eventually get to the point where new projects aren’t daunting to set up at all! I’m not quite there yet, but I hope to be soon!